|

|

| << PREV |

|

|

The clearest evidence would be requisite

[required] to make any sane man believe in the

miracles by which Christianity is supported, --

that the more we know of the fixed laws of

nature the more incredible do the miracles

become.

CHARLES DARWIN (1876)

(In Barlow 1958, 86)

The black smoke and flame of the funeral pyre curled about the pallid corpse of what twelve days earlier had been a brave young soldier defending his city in battle. As the bereaved father, Armenius, stared vacantly at the mortal remains of his future hopes, they suddenly stirred to life, and the body of his son leapt from between the flames and shouted, "Don't be afraid, I have much to tell you." He did indeed, and Er's account of how his soul left his body, traveled through another world, and then was sent back to relate what he had seen and heard has been passed down through history and may be found at the end of Plato's great dialogue The Republic (1974 ed., 447).[1]

This purported event is clearly miraculous, but it is not isolated; modern examples have been reported by Rawlings (1978), a medical specialist in cardiovascular diseases. He points out that with today's resuscitation techniques, an increasing number of individuals are returning from that clinically gray area between life and death, some to report heavenly experiences while others recount tales of terror. Fascinating though these accounts may be, however, a recitation of the details would be inappropriate in this context. But two observations can be made: First, the experiences reported by individuals alleged to have returned from the dead lie beyond any proof. That is, the experience cannot be repeated and studied in a laboratory. Moreover, the experience is not accessible to a second observer. And second, since there can be no proof, the acceptance of such accounts by others becomes a matter of faith and, logically, outright rejection is also a matter of faith since the testimony of the only witness can neither be proved nor disproved. Credibility of the storyteller naturally plays no small part in establishing belief in the minds of those receiving the account. Doubtless, as the story becomes further removed in time and distance from its source, skepticism becomes more the rule than the exception. Nevertheless, the historical record shows that mankind has essentially fallen into two camps consisting of those who are prepared to believe in the unprovable, such as the survival of human personality after physical death, and those who demand proof before belief. The latter camp has generally been in the minority but is somewhat augmented by those of undecided opinion.

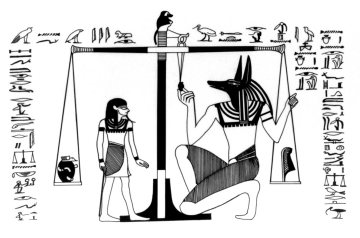

Ancient Egyptian belief in the immortality of the soul:

the soul of Ani depicted

as the Ba bird visiting his mummified body. (After illustration

to spell 89 of the

Egyptian Book of the Dead; Kathy Stevenson)

Once a position of belief in this unprovable concept has been taken, the matter then becomes more involved. In essence, what is really being admitted by belief is that there is a dimension that is as yet beyond man's reach for inquiry. When pressed further, the accounts, such as the one given by Plato, also make two further important points. The first is that in the other world each soul is held accountable to a Superior Being for actions committed during mortal life. The Zoroastrians of Persia, for example, believed in an existence beyond the grave and spoke of a future resurrection and judgment. The idea of reward and punishment in the next life is not only worldwide but has been very common throughout history (Durant 1954, 1:371). The second important point is that the Superior Being, variously called the Divine Spirit or the Creator, is the great intelligence responsible for the design, creation, and maintenance of the universe, including the earth and its inhabitants. This belief will be recognized as "religion", which has taken on a multitude of forms but which throughout history has been based on faith in such evidence as that offered by individuals returning from a death-like state. Acknowledging that there are many shades of belief, the clear distinction should be made that evidence is not proof; until proof is forthcoming, faith will still be necessary.

Egyptian belief in judgment after death: the judgment

scene in this papyrus of

Hunefer shows the soul as the heart being weighed against

an ostrich feather.

(After illustration to spell 30b of Egyptian Book

of the Dead; Kathy Stevenson)

The other camp of opinion, which rejects the accounts of life-after-death experiences, usually does so with the argument that since the claims for the supernatural dimension are not open for investigation -- that is, are not repeatable and observable -- it is better to adopt the safe position of no opinion, or, more boldly, deny the whole issue. The personal accounts are usually rationalized away by claiming the experience to be one of self-generated images under death-like circumstances. But what is really implied is that the whole unprovable notion of a supernatural dimension with a Superior Being having roles of Designer, Creator, and Judge is in fact a delusion. As we shall see in the final chapter, those formally committed to these views have actually made this a statement of creed. The more commonplace principle of design in nature, traditionally seen as evidence for a Designer, is also rationalized by naturalistic explanations according to what are seen as the fixed laws of nature. Charles Darwin expressed this same view and was quite unable to accept the possibility of divine intervention of the fixed laws of nature -- that is, of the miraculous. A few before Darwin and many since have held to this same opinion, which ultimately has to reject all the unprovable biblical accounts from the Virgin birth to the supernatural creation of the universe.

Naturalistic explanations are offered to explain away the miraculous

but, as we shall see throughout the subsequent chapters, these are often

not really explanations at all. For example, a moment's thought given to

the popular big-bang theory for the origin of the universe will show that

it fails to account for the supposed highly-ordered primordial egg in the

first place. Indeed, in the matter of origins, faith in the explanation

offered is essential since there were no eye-witnesses to what actually

happened nor can the event be repeated in a laboratory. Nevertheless, for

those who find the miraculous difficult to accept, the rationalistic explanation

provides a measure of intellectual satisfaction.

Revelation and Belief

Once more taking as our example of an unprovable event the accounts of those returning from the near dead state, there is undeniable evidence that our most remote ancestors at the dawn of human history believed in the survival of the personality after death. Neanderthal man buried his dead with flowers and ornaments indicating belief in some kind of after-life. From ancient Egypt to Tibet, from Babylon to China, there has been a committed belief to a life after death and this belief has been carried forward into modern times through the Jewish, Islamic, and Christian faiths. There would seem to be little doubt then that belief in an after-life has been universal since the earliest times.

It is a fair question to ask how this belief came about in the first place and why it is universal, for it must surely have some established basis and not be merely the result of wishful thinking. It is reasonable to suggest that the belief originated and has been reinforced throughout history by individuals returning from the dead, or near-dead state, to tell of their experience. Plato's retelling of Er's account is one such example. If this is true, it can be said then that these reports are revelations of knowledge not available to our natural senses. The Bible, sacred to Jew, Moslem, and Christian, has much to say about the eternal nature of man's soul and actually reports eight cases of resuscitation.[2]

Although this is one of the more spectacular forms of revelation, there

are other biblical revelations equally as important, ranging from the origin

of the universe and mankind in the first few chapters to our ultimate destiny

in the last. All this is revelation of knowledge not available to us by

natural means and which must be accepted on faith. The acceptance or rejection

of this revealed knowledge has throughout history been one of the root

causes of divisions among mankind. It divided the Greek philosophers. It

divided Europe at the time of the Reformation. And it is still dividing

people today because there will always be those who believe and experience

their belief and others who wait in vain for proof that never comes.[3]

Our Greek Heritage

The Greeks contributed a great deal to the corpus of human knowledge in our Western hemisphere and are credited with laying much of the foundation of our heritage. The remainder of the foundation was adopted from the old nation of Israel and forms the Judeo-Christian part of our heritage; more will be said of this later in this chapter. Greek thinkers, rather than, for instance, Arab or Egyptian, have been responsible for our Western mind-set for two principal reasons: First, because their written records have survived in readable form. The Egyptian hieroglyphics and the Babylonian cuniform, for example, were discovered and deciphered only within the last century and a half. Secondly, the writings of Aristotle concerning the natural sciences and those of Plato regarding metaphysical speculations and political ideals have been taught in the West for almost two thousand years. For example, Plato's Academy taught his ideas from the 3rd century B.C. to the 6th century A.D. This effectively established neo-platonism in the Christian Church in the fourth century and the Revolution in France in the eighteenth century.

Among the Greeks, Socrates, Plato, and particularly Aristotle stand

preeminent as the shapers of the philosophical tradition of the West. Socrates

(fifth century B.C.) was a great teacher, using a technique of question

and answer that has since become known as the Socratic method. All that

is known of him has been related to us through two of his disciples, Plato

and Xenophon. He believed profoundly that the universe is under the control

of a single Divine Spirit, while the human soul is immortal and meets with

judgment and retribution in the other world. His conviction of faith no

doubt resulted from his belief that he was the recipient of warnings addressed

to him by the Divine Voice (Taylor 1975, 45).[4]

However, in teaching his views he raised many awkward questions that challenged

the polytheistic (many gods) beliefs of the day. The authorities accused

him of corrupting the youth and condemned him to die by hemlock poisoning.

In this, he was probably being made the scapegoat for the political ills

of the day. Attitudes have not changed a great deal since Socrates' time,

although an actual cup of hemlock is no longer offered.

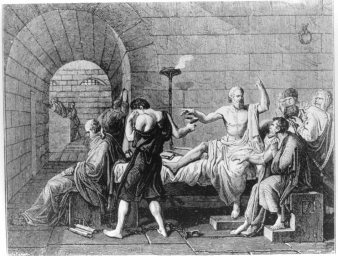

Death of Socrates. Socrates, 469-399 B.C., confounded the vanity of the sophists and the fallacy of their doctrines while he exposed the folly of the many gods the Greeks worshipped. Jacques Louis David, the French painter of this well-known scene, has captured the last moments of Socrates as he discourses to his disciples on the immortality of the soul, absorbed in reflections while the bowl of hemlock is being regretfully offered to him. Plato was absent for this tragic event. (Drawn after the painting by W. Cooke, c. 1807; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

As a student of Socrates, Plato was deeply impressed by his teacher's confidence in the certainty of his destiny when faced with the death sentence (Tredennick 1962, 99). Plato's inherited belief in an afterlife was reinforced a decade later during his visit to the Pythagoreans in southern Italy. The Pythagoreans also believed in an afterlife. It is thought that Plato received the account of the young man, Er, from them. In Plato's day, government largely took the form of city-states. From his observations of the general anarchy and corruption, not only in his own city of Athens but also in other countries, Plato concluded that none were working for the common good. He drew up a proposal for an ideal city-state governed by true philosophers (wise men) and set this out in the form of a dialogue in his Republic. |

What Plato outlined has been taken by some educators to be a model for Utopia. To ensure that future generations are directed towards that noble end, the Republic long ago became part of the required reading in liberal arts courses. The atheist philosopher Bertrand Russel (1949, 30) pointed to Soviet Russia as the state most closely run on Platonic principles, while if this is true then Plato's Republic advocates slavery for everyone except for the elite few. However, careful reading of the Republic shows that the entire hypothetical system hinges on the virtue of its rulers. Plato expressed doubt that his ideal society would ever exist on earth although he felt such a scheme is "laid up as a pattern in heaven" (Plato 1974 ed., 420).[5] He concluded that it would be "better for every creature to be under the control of divine wisdom", that all men may "be friends and equals" (Plato 1974 ed., 418).

Plato's inclusion of Er's account of the immortality of the soul may at first seem incongruous in a dissertation about politics, until it is realized that his temporal Republic is only a temporal form of an eternal city-state which he visualized as existing in the other world.[6 ] His ideal State on earth would then only be possible when both rulers and citizens have a vastly different moral ethos from that of the human condition today. Clearly, Plato had no concept of the Fall of Man while the totalitarian regimes based upon his ideals today make it perfectly evident that power corrupts -- (Plato 1974 ed., 50).[7] His teaching of the immortal soul followed from his belief in reincarnation.

More than a thousand years before Plato's day, the old nation of Israel also struggled with the concept of rule from above and eventually appointed King Saul (about 1050 B.C.) to be responsible for ruling according to received divine wisdom. This was the beginning of the divine right of kings, or rule by revelation, and was passed on to Judeo-Christianity. Judeo-Christian societies still carry vestiges of this type of rulership. The dismal record shows, however, that the fine dividing line between divine revelation and man's reason, between divinity and dictatorship, has been crossed all too often. In succeeding chapters, the dream of an ideal state using Plato's Republic as a model will be found to develop with the rationalist view of science and finally become reality, in name if not in fact, in societies established by revolutions in France, Russia, and China.

Plato founded the first recognizable university, but this arose out of the already existing practice of learned individuals hiring themselves out to teach the young. These teachers were known as "sophists", a word that originally meant "wise-man". But over the years these teachers emphasized the art of winning the argument over finding out if there was any truth to the argument in the first place, with the result that entirely specious arguments were often won purely by the force of rhetoric. The word "sophist" then came to mean "deceiver". Our modern word "sophisticate" is derived from this and conveys a meaning of being "worldly-wise"; root words such as these might lead one to the nagging suspicion that deception and the world's wisdom thus have something in common. Protagoras (fifth century B.C.) was one of the leading sophists of Plato's day. In complete contrast to the views of Socrates or Plato, he could not accept the belief in a supernatural dimension with immortal souls and a Divine Being. For Protagoras, man was the measure of all things, and in an imaginary dialogue between Protagoras and Socrates, Plato (1970 ed.) cleverly played these two opposing beliefs -- theistic and atheistic -- against each other. The views of Protagoras run as a thread throughout history, and, as we shall see in the final chapter, they eventually mushroom out as twentieth century humanism.

Aristotle also had an important influence on Western thought. His early

ideas were not unnaturally those of his teacher Plato, with whom he spent

twenty years as a student. At this time he believed in the immortality

of the soul and a monotheistic (one God) view similar to Plato's belief

in a Divine Spirit. Later, when working for Alexander the Great, Aristotle

built up an enormous body of knowledge, which he was largely successful

in systematizing -- after his own fashion. He produced a vast number of

works on logic, metaphysics (theology), natural philosophy (today's biological

and geological sciences), ethics, politics, and even poetry, all the time

rationalizing and fitting everything into his neatly ordered system. During

this period of intense rationalism, in the latter half of his life, he

began to take on a mechanistic view of the world; his belief in an unproven

immortality of the soul diminished and, with it, any idea of divine wisdom

and revelation to man.

| With growing disbelief in an afterlife, it was but a short step to reason that if the soul were not immortal then it must be mortal and, therefore, would not separate at bodily death but would follow the mortal remains into oblivion. The notions of what constituted oblivion were sketchy and varied among the Greeks but, in any event, could hardly be said to offer any hope. Socrates' belief in a Divine Spirit who was keenly interested in the affairs of nature and men, became for Aristotle merely a prime mover who set everything in motion, and then, like an absentee landlord, left it all to take care of itself. Aristotle recognized that there was great order in the living world, which seemingly graduated as a scala natura, or living ladder, from the smallest creature at the bottom to the prime mover at the top. Aristotle (1965 ed.) thus found it difficult to believe that a single great intelligence could direct every day-to-day detail. He reasoned that the Creator had given to every living thing, even to individual organs, a ideological principle, or built-in purpose, so that throughout all time each organ would develop according to a plan. Significantly, liberal commentators such as Balme (1970) deny this and stress that Aristotle appealed to chance, thus reinforcing the historical background to the theory of evolution. A close reading of Aristotle's Physics, however, makes it clear that he specifically excluded chance as a factor working for the good of nature (Aristotle 1961). By ascribing a purpose to nature, Aristotle gave nature a characteristic of the deity, and, in a subtle way, this has tended to redirect men's attention towards the complete personification and even deification of nature itself. The historian Hooykaas (1972) has shown that Charles Darwin continually personified nature with remarks such as, "natural selection picks out with unerring skill the best varieties" (p. 18). These remarks even brought a gentle rebuke from his friend Charles Lyell -- but all this is a long way from our present subject, the Greek philosophers, and will not be reached until Chapter Fourteen. |

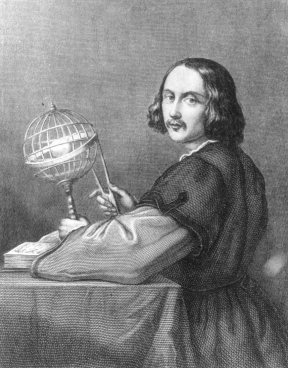

Aristotle, 384-322 B.C. Reduced the role of God to that of an absentee landlord. (Engraving by Leroux after the sculpture by Visconti; Academy of Medicine, Toronto) |

Finally, Aristotle's great sense of appeal to reason based on experience of reality and systematic research led him to abandon Plato's concept of knowledge acquired by revelation. In this he was left with the earlier view of the mystic Empedocles (fifth century B.C.), that knowledge is only received through man's five senses -- hearing, seeing, touch, taste, and smell. Although this is perfectly logical for the physical world, by its very nature this limits the acquisition of knowledge to the physical world and denies any other dimension. Plato was aware of another channel, an ineffable sixth sense, which was later noted by psychologist William James (1902, 371) as a state of knowledge and yet incommunicable in ordinary language.

Although Aristotle's work appealed to reason, it was based on much speculation

and less on his own good advice of observation and experiment. For example,

although he was critical of Empedocles' theory that all matter consists

of four elements: fire, air, water, and earth and that each of these in

turn was supposed to possess two of four basic properties: hot, cold, wet

and dry the fact that Aristotle's writings survived led to this nonsense

dominating and delaying the progress of science from the 4th century B.C.

to the 17th century A.D. In retrospect, it can be seen that this was primarily

because his explanations seemed so reasonable at first sight.

The philosophy of Democritus, who was known to have died in 362 B.C. and was probably a contemporary of Leucippus, denied a Creator and gave chance a creative faculty. A man of intellect and wealth, he mocked the less fortunate. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Arising from the most remote period of Greek history, sometime in the

sixth century B.C., came Democritus, credited as the founder or co-founder

with Leucippus of the school of atomistic philosophy. Democritus' view

rested on the doctrine that the universe is composed of vast numbers of

atoms, mechanically combined. This remarkably modern-sounding atomic concept

of the physical universe described the physical universe as operating by

chance with no place for supernatural intervention. After this philosophy

was established, Epicurus, a contemporary of Aristotle, recognized that

chance events could not operate under static conditions. He proposed that

movement was a vital factor. In this way, blind chance was given a creative

ability. We shall see in later chapters that this movement becomes the

process of natural selection in the theory of evolution. Epicurus further

claimed that foolish superstition is rooted in the belief in the supernatural

and that to banish this belief would at once rid men and society of superstition

and notions of divine intervention. Wise conduct of life, he said, was

better attained by abandonment of religious beliefs with reliance better

placed in evidence attained through the five human senses. Thus began the

Epicurean philosophy.

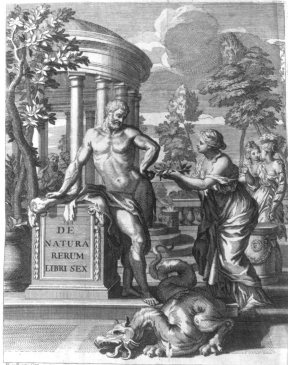

At a later time and in a different place -- the Greek empire having collapsed in the meantime -- Lucretius Cams (99-55 B.C.), of Rome, eloquently combined the ideas of Democritus and Epicurus in his monumental poem De Natura Rerum, that is, On the Nature of the Universe. The purely mechanical and atomistic world of Lucretius had no place for a supernatural dimension with an intervening deity. Everything obeyed the inexorable laws of chance and nature. In spite of his apparent denial of the Deity, Lucretius nevertheless began his thesis with a dedicatory prayer to the creative force of nature personified as Venus, goddess mother of the founder of the Roman people (Lucretius 1951 ed., 27). This Latin classic remained as a few treasured scrolls in the hands of the scholars until the invention of the printing press in the fifteenth century. It then became required reading first in Latin; eventually, an English translation followed. Today, it is still required reading in many liberal arts courses. |

In summary, the prevailing views among the Greeks, later adopted by

the Romans, fell into two camps. The theists, exemplified by Socrates and

Plato, believed in supernatural revelation such as the accounts of those

returned from the dead. Thus they believed in the immortality of the soul

and a Divine Being. Some others, such as Protagoras, were outright atheists,

but many, like Aristotle, accepted God but denied revelation and the immortality

of the soul (Blackham 1976).[8]

In the seventeenth century this latter view became popular among certain

Western intellectuals and was known as Deism. These primary beliefs in

the nature or even absence of God affected the peripheral views of individuals

in each camp and inevitably led to the development of differing views on

the creation of the world. Plato (1937 ed.) gave his account of divine

creation in his Timaeus,

while Lucretius summed up the mechanistic

view in his On the Nature of the Universe. By the time of Lucretius,

the Roman and Greek worlds were filled with every cult known to man while

the Deist teaching of the inseparability of the body and soul had by then

become universal. The Roman poet Horace (65-8 B.C.) captures this depressing

view in these lines to his friend Torquatus:

Lo! the nude Graces linked with Nymphs appear

In the Spring dance at play!

No round of hopes for us! So speaks the year

And time that steals our day.Yet new moons swift replace the seasons spent;

But when we forth are thrust,

Where old Aeneas, Tullus, Ancus went,

Shadow are we and dust.Once thou are dead, and Minos' high decree

Shall speak to seal thy doom --

Though noble, pious, eloquent thou be,

These snatch not from the tomb.

(Horace 1911 ed., 101)

Horace expresses the view that unlike the immortals (nude Graces,

etc.), man is mortal and has a limited life span. When we die, we return

to dust, and no matter how good we may have been in life, nothing can raise

us from the dead.

| Our Jewish Heritage

In complete contrast to the Greeks and Romans, the descendants of Abraham had an unquestioning faith in one Divine Being and hope of an afterlife in an eternal paradise. The entire structure of Jewish life, whether in Israel or in exile, had always been tightly knit and introspective, with lives regulated daily by the Mosaic rules and regulations, by the priests and the perpetual succession of feast days, intended as reminders of their past. They believed that their laws had been given by the Deity himself to their patriarch Moses and were thus a divine revelation; absolute obedience to the law was essential to ensure a heavenly destiny for their souls and was seemingly a promise made exclusively to the descendants of Jacob. With the promise of this afterlife, and the assurance of the certain loss of it by disbelief and excommunication, belief in the law was self-sustained. Moreover, since they believed the same divinely inspired author had penned the account of the Creation of the earth and the subsequent judgmental Flood, it was not difficult to include this within their belief system. |

Title page to 1743 edition of On the Nature of the Universe in Six Books by Lucretius Carus, 99-55 B.C. (Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

Then came a certain carpenter from Nazareth. He spoke of the supernatural dimension and the Eternal Being from personal experience and openly demonstrated divine overruling of the natural laws. The claim to his miraculous birth could be questioned, but his subsequent death and resurrection clearly defied the natural laws. It was the Resurrection that proved to be the greatest stumbling block to the Greeks, but even more upsetting to the Levitical priesthood was his claim to be the Son of God and his criticism of their embellishment of the Mosaic law (Acts 17:31-32). Their very livelihood was threatened when he raised awkward questions about the priesthood before the crowds, so, like Socrates, he was condemned to death, not by a cup of hemlock but by the Roman cross. At the same time there were those who believed that not only was there a more certain way, other than the Jewish tradition, of attaining the eternally blissful life, but also that this was possible without subservience to priests and all their rules and traditions. Vested interests were at stake. The final blow to the orthodox Jewish mind came when it became known that the promised afterlife was not the exclusive preserve of the Jewish lawkeeper but available to everyone (Acts 22:21-22). Clearly, such ideas were a threat to the Jews' community life and even to their nationhood; persecution against the followers of Jesus had to be engineered from within or without -- after all, the whole upstart movement was seen to be based on a blasphemy.

Christianity grew out of such beginnings. The first converts were Jews,

but within a few years non-Jewish followers were converted. The ancient

writings of the Jews, including the Mosaic Creation account, were adopted

by the early Christians. For these people, from all walks of life and all

nationalities and ages, revelation was something experiential. Miraculous

events continued to be a reminder that the deity was pleased to intervene

in the affairs of men and often overruled the natural laws to do so. Eventually,

the movement became widespread throughout the Roman Empire. Some in high

office saw the Christians as responsible for creating public awareness

of the corruption in government. The government falsely accused the movement

for its own failures and set up a massive persecution of the Christians

as a spectacular way to divert public attention from their own mismanagement.

Much to the chagrin of the oppressors, victims, like Socrates, had an inner

assurance of their destiny and went by the thousands to a fearless death

in the Roman Circus.

Christianity and Science

The history of science, which has an all-important place in our lives

today, is intimately related to the belief systems of the individuals associated

with its various discoveries. During the past two millennia, the greatest

scientific achievements have been made in the Western hemisphere, against

the background of the Judeo-Christian belief system. The history of science

and the history of Christianity thus overlap, and it is important to know

something of the one in order to understand the other. For this reason,

the rationale behind such topics as Darwin's theory of evolution or space

exploration is intimately related to the prevailing historical belief system

at the time of their conception. The presentation of history, particularly

in school textbooks, seems intended to be instantly forgotten, with dry

lists of names and dates and the who and when but seldom the why. Some

more forthright historians, such as Stanley Jaki (1978), have pointed out

that one of the failings of their profession is that historians have a

tendency to select historical facts to promote their own preconceived views,

which are usually antagonistic to Christianity. Jaki gives, as an extreme

example, Voltaire's massive universal history, which both ridiculed historic

Christianity and glossed over its significance:

The unscholarly character of Voltaire's account of history can easily be gathered from the fact that he mentioned Christ only once, and by then he was dealing with Constantine's crossing of the Milvian Bridge. Not content with turning Christ into a virtual nonentity, Voltaire was also careful to disassociate Christ from historic Christianity. The fury of his sarcasm would certainly have descended on anyone trying to establish a positive connection between Christian theism and Newtonian science (Jaki 1978, 315).

However, one does not have to reach back to Voltaire to find slanted

historical accounts. Young (1974) has recently given unsparing exposure

of the fallacies and hypocrisy present in the efforts of two of today's

liberal historians, Lynn White and Arnold Toynbee, who blame Christianity

for the impending disaster in ecology.[9]

Finally, historians are reluctant to recognize that the explanation

of the workings of nature -- that is, natural science -- coincided with

the historical reinstatement of the original Christian belief in divine

revelation. Jaki documents, at some length, the connection between community

belief system and innovation in science. In an example from a much earlier

age, he quotes contemporary science historian Joseph Needham who, in spite

of his avowed Marxism, conceded that Chinese science drifted into a blind

alley when the Chinese belief in a rational Lawgiver or Creator of the

world vanished. "Lacking that belief, the Chinese could not bring themselves

to believe that man was able to trace out at least some of the laws of

the physical universe" (Jaki 1978, 14). One should therefore approach the

history text, academic or popular, with questions about the author's background

and beliefs: Is he conservative or liberal, right-wing or left-wing? Many

seem to fall into the latter category. In this necessarily brief overview

of our Christian and scientific heritage, it is only fair to state that

this author makes his approach from the right.

The Latin Church

In its initial stages within the Roman Empire, Christianity suffered constant persecution from the civil authorities. At the same time, the Roman Empire was crumbling from corruption from within. Finally, in A.D. 312 at Milvian Bridge during one of the innumerable battles against the enemies of Rome, emperor Constantine reversed his position against the Christians and formed an alliance to promote their cause -- by force of arms if necessary! Constantine ascribed his actions to supernatural intervention.[10] Until this time the church had largely been an underground movement, and the local leaders or bishops had known only spiritual power. Now, one of these bishops in Rome was bequeathed with secular power by Constantine. It turned out to be a curse rather than a blessing. The election of each new head of the church, later called pope, became a matter of power politics, and for the next seventeen centuries papal election was beset with bloodshed, corruption, and intrigue (Martin 1981). Originally, the election of a Christian leader was by consensus of the people; in this way it was believed to be the will of God. The notion was expressed as vox populi, vox dei -- the voice of the people is the voice of God. It is evident that under Constantine's curse God had very little to say in the voice of the people! Nevertheless, subsequent ideas of democracy in Europe and America have been founded on this principle and have suffered at the hands of those who have sought to control the government and, thus, the people.

The Latin church, now freed from persecution, began full of faith and life, but with growing secular power it began to corrode from the top down. For the most part illiteracy was the greatest problem. Even among the handful of Western scholars, very few could read the Hebrew and Greek of the original Bible, and their knowledge was confined to Jerome's Latin translation. Various fanciful interpretations were made, which eventually became dogmas, while the original message was becoming hopelessly lost to priest and layman among the allegories and traditions. The greatest allegorizer of all was Origen, A.D. 185-254 (Shotwell 1923, 291).[11] The Dark Ages, between A.D. 400 and 1400, were difficult times especially for Europeans, and it is little wonder that there was no scientific progress during this time. Barbarians had swept away the Roman Empire, scholars had been burned together with their books, and, while lawlessness reigned in the countryside, plagues took the lives of millions in the towns and cities. During this time church traditions were introduced, miracles were contrived, and holy relics appeared by the ton in order to maintain the faith (and financial support from the uneducated). Often overlooked, however, is the fact that during this same time the church built hospitals, provided the only education available, and began the universities of England and Europe.

To add to the general misery of the Dark Ages, the Moslem Arabs began a conquest of Europe in A.D. 622. The Arabs within the great Islamic empire became the masters of science, preserving the medical works of the Greek physician Galen (A.D. 130-200) and the scientific works of Aristotle, both of whom had made gross errors that would hinder progress for another thousand years. Not all the Arab scientists of the day were Moslem: many were Christians, Jews, or Persians writing in Arabic. The West is indebted to Islam for certain medical advances, the concept of "zero" in mathematics, and even the numerals we use today; otherwise we might still be struggling with Roman numerals (Edwardes 1971, 52; Goldstein 1980, 97).[12]

Slowly, educated men arose from within the Latin church. By working

with Arab scholars, the classical Greek works that had been preserved in

Arabic were translated into Latin. By the twelfth century the ideas of

the Greeks, and Aristotle in particular, became more widely available and

influenced Western thinkers. The old Latin church, full of tradition and

superstition though it was, took another turn for the worse.

Architect of the Roman Church

After so many years of intellectual darkness, the more advanced works of Aristotle, such as On the Soul, Physics, and Metaphysics, became available to Western scholars, in A.D. 1200. Aristotle presented a complete explanation of reality, without any reference to a personal God. That is, there was, according to Aristotle, no divine intervention in the affairs of man or nature. In this he challenged Christian and Islamic theology and strained Jewish faith as well.

All these beliefs were based on biblical revelation, which said, for

example, that the physical universe had a beginning and it will have an

end. Aristotle taught that it was eternal with no end and that history

was an endless cycle of existence, striving to be like the "Unmoved Mover"

but never reaching its goal. As we have discussed earlier, he also denied

the immortality of the soul. Many scholars, Arab, Jewish, and Christian,

could see the potential danger of such a belief system and condemned Aristotle's

works. On the other hand, his natural philosophies seemed so attractive,

like wonderful revelations of truth from a glorious bygone age. The impact

of Aristotle's works on the twelfth century mind has been compared with

the impact of Darwin's work in the nineteenth century. Both were outwardly

attractive, appealing to reason, but both were also at complete variance

with scriptural revelation

Thomas Aquinas, 1225-74. Introduced humanism to Christian theology and laid the foundation for the doctrine of indulgences that eventually brought about the Reformation. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Thomas Aquinas, born in Italy, became a Dominican monk, studied in Paris, and spent the rest of his life teaching there and in Italy. Known in his student years as "dumb ox" because of his bulk and slowness, he has since become almost universally known as the sainted theologian. Perhaps to establish that the blessing of heaven rested upon his labors, there is a legend that as he knelt one day before an image of Christ on the cross, the image spoke to him saying, "Thomas, thou has written well concerning me; what price wilt thou receive for thy labour?" This is a typical tradition from the day and raises the interesting theological problem of the deity's purported response to Aquinas doing what had been expressly forbidden in flagrante delicto; nevertheless, he had labored well. There is no question that Aquinas was one of history's intellectual giants, and scholars today are impressed by his rigor, complexity, and subtlety of thought. But he was, after all, trying to reconcile the irreconcilable -- Aristotle's naturalism and biblical super-naturalism; his efforts for doing so occupy eighteen large volumes (Magill 1963). The result was that Greek philosophy could only be harmonized with biblical theology at the expense of trimming the latter to fit the former. For example, on the question of the origin and destiny of the universe, belief in Aristotle's unending eternity or in the biblically revealed finiteness demands faith for their acceptance in both cases, since there can be no proof for either view. Harmonization inevitably finished up being true to neither and left the door open for bias.[13] |

Many of Aquinas' views were not accepted in his own time, but once the

door of revelation had been opened to human reason, God became in people's

minds removed further from his creation, and man was left to rely on his

own intellect. Greek humanism had thus been introduced to Christian theology.

Doctrines concerning theology only shift as fast as can be accepted by

the cloistered ranks of clerics, and it would be another three centuries

before the thoughts of Aquinas were officially adopted at the Council of

Trent. It took a further three centuries before posthumous sainthood and

Pope Leo XIII's declaration, in 1879, that Aquinas's theology is eternally

valid. Aquinas's theological system, known as Thomism, today directs the

beliefs and lifestyle of more than 600 million of the world's Roman Catholics.

| The Latin Church Divided

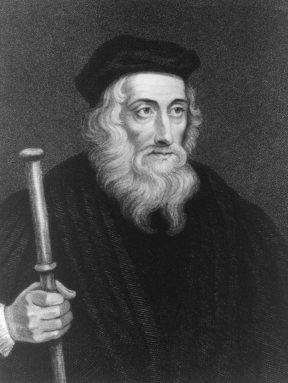

From the time of Aquinas in the twelfth century, the old Latin church was headed towards the great schism in Christianity. If dates were to be attached to such events, the Council of Trent, held between 1545 and 1563, marks a convenient formal dividing point. Arising out of the obscurity of the Dark Ages, the scholar John Wyclif, in England, recognized that the people of the Latin church only knew of their faith what had been told them by friar and priest. As a result, all kinds of abuse had been introduced in the name of eternal salvation. Bibles were the preserve of the monastery priest, rarely read, and when they were, only in Latin. Wyclif translated the Bible into English. Since it would be another century before the invention of the printing press, he had copies written by hand and made available to the people -- the beginning of a period in which men began to find out for themselves what the Bible actually said, and did not say, in contrast to what they had been taught. At the same time, Latin copies of the Greek philosophers were becoming available to scholars, and the opposing theological positions began to harden. The church authorities were concerned, not only that awkward questions were being raised but, worse, that coffers were being threatened. To make an example of these "heretics", some were publicly burned at the stake together with their Bibles.[14] Christian persecution was beginning again, and it originated from the same city -- popes had merely replaced emperors. |

John Wyclif, 1324-84. Made handwritten Bibles available to the people and began a revival across Europe. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

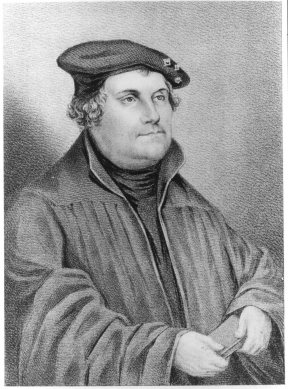

Later in Germany Father Martin Luther, a professor of theology at the

University of Wittenburg, grew distressed over his church's teaching of

the purported relationship between financial contribution to the church

in this life and the destiny of the soul in the next. His reading of the

Bible led him to be convinced that God could not be understood with the

natural senses and the human reasoning of Aristotle but only by that "sixth

sense", that secret the early Christians spoke of as "revelation". Like

Wyclif, Luther had his hand on the Reformation door that eventually led

to the formation of the Protestant church; the date was 1517.

Johann Gutenberg, 1400-68. Gutenberg's new method of printing, introduced in 1446-48, used movable metal type rather than having a hand-carved plate for each page. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Martin Luther, 1483-1546. Rejecting all theology based on tradition, he emphasized that God reveals the truth by the reader's faith in the Bible. (Lithograph by Houston; Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

Luther lived after Johann Gutenberg had developed the movable type printing

press, and it was therefore less of an arduous task to get Bibles to the

common people in their own tongue. As with Wyclif's revival a century and

a half earlier, many came to discover experien-tially that they could receive

knowledge of God and his creation by revelation through the pages of the

Bible, but more than that, that they could tell false knowledge from true

with absolute certainty. This was a powerful tool in exposing the false

teachings of the Latin church. It became painfully evident to the Vatican

hierarchy that the Reformation movement could not be extinguished by persecution.

Neither the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition instituted in 1542 nor

later the book censorship by the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index

of Forbidden Books) could stem the spread of Protestant Reformation doctrines.

A Counter-Reformation movement within the mother church then began, culminating

in the Council of Trent. Here, many of the old abuses were cleared away,

and a doctrinal position based upon Aquinas's theology was spelled out

in detail. This marked the beginning of the Roman church as it is known

today and, with it, recognition of the Protestant movement, which had a

significantly different doctrinal position. The Roman doctrine was essentially

what had grown over the centuries within the Latin church and was based

primarily on tradition and the authority of the pope. The Protestant doctrine

differed by degrees from the simple nonacceptance of the pope to complete

abandonment of all that was not authorized by the Bible. Liberal historians

are often unable to sort out these differences and, as we shall see in

the Galileo affair, blame the whole of Christianity from that time to the

present for obstructing the pathway of science.

The Galileo Affair

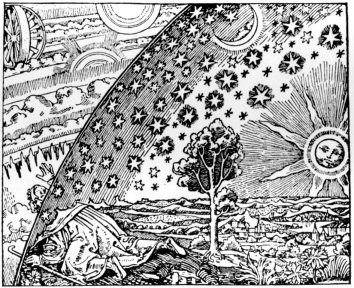

Perhaps the most notable conflict between Christianity and science, and by this we mean the Roman church's hierarchy and the developing humanistic pursuit of knowledge, came to a climax in 1633, at the trial of Galileo Galilei in Rome. Much has been written about this affair, and doubtless more is to come; Bronowski (1973, 214) maintains that the Vatican archives still hold unrevealed documents. In Galileo's day the orthodox view of the cosmos was established according to the science of Aristotle, which had been incorporated into theological doctrine by Aquinas. However, an intervening hand from Egypt had played a part in constructing the medieval portrait of the heavens.

Ptolemy's A.D. 85-165 crystalline spheres of heaven was

a notion adopted and taught by the Latin Church to support

its biblical interpretation that the earth was fixed

in space.

(c. 1500; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board)

Ptolemy of Alexandria (A.D. 85-165), not to be confused with Egyptian kings of the same name, was a follower of Aristotle and believed that the stationary earth stood at the center of the universe while the moon, planets, sun, and all the stars revolved about the earth in a series of inter-nesting spheres. He visualized each hollow sphere as being made of transparent crystal into which was fixed the heavenly bodies; thus, as the spheres revolved, these bodies were transported in their respective circuits. Ptolemy's works were among those inherited from the Arabs and his views came to be adopted by the Latin fathers. Although the Bible is not specific about which revolves about what, they found Scriptures such as, "(The Sun) His going forth is from the end of heaven and his circuit unto the ends of it" (Psalm 19:6), which seemed to offer support for the notion.[15] Eventually, the geocentric or earth-centered view became crystallized into dogma and was held to be as sacred as the Scriptures it was seen to support (Campanella 1639). However, churchmen of that age were not as ignorant as we have sometimes been led to believe. In his criticism of this attitude, C.S. Lewis makes the statement, "You will read in some books that men of the Middle Ages thought the earth was flat and the stars near but that is a lie" (Lewis 1948, 3). Strong talk, but then A.D. White's classic put-down, A History of the Warfare of Science With Theology in Christendom, would certainly have inspired Lewis's reaction. Nevertheless, the great crystal spheres were seriously considered by scientists of such stature as Johannes Kepler, who actually wrote music based upon the calculated ratios of the motions of the heavenly bodies. (A more musically successful and lasting attempt survives today in the beautiful Josef Strauss waltz "Music of the Spheres".)

While the notion of Ptolemy's spheres had been ingeniously blended with

theology by the poet Dante,[16]

others, such as the Polish Latin scholar Nicholas Copernicus, were having

serious doubts (Milano 1981). Copernicus had no telescope, but from his

observations he concluded that it made more sense to place the sun rather

than the earth at the center of our planetary system. He was careful to

keep these ideas to himself, but in 1543, near the age of seventy, he published

his mathematical description of the heliocentric system -- and conveniently

died the same year.

| Galileo Galilei was a short, active, and very practical man employed as a professor of mathematics in Venice, which at that time was not a romantic tourist spot but the center of the world's arts and commerce. Galileo had read the published work of Copernicus and had built his own small telescope, which had only recently been developed in Holland.[17] In 1610 he was the first man to see the theoretical work of a great scientist of half a century earlier -- Copernicus -- confirmed by observation, and he naturally wanted to tell the world about it. Unfortunately the world, or rather a few men of the Roman church hierarchy, were not yet prepared to accept this news. He was told to keep quiet. Keep quiet he did. He was no doubt influenced by the memory of fellow scientist Giordano Bruno's condemnation by the Inquisition to burn at the stake on the Campo dei Fiori in Rome. Orthodox history has made Bruno a martyr for science. The truth of the matter is that he was not condemned for science but rather for occult practices, a common though infrequently reported activity among the illustrious names of science (Yates 1964). Galileo waited patiently another twenty-three years before publishing his findings. The infamous trial took place the following year in 1633. After making a written recantation of his work, he was confined to house arrest for the remainder of his days. |

Nicholas Copernicus, 1473-1543. Refuted Ptolemy's geocentric system and proposed the heliocentric system we accept today. (Engraving by Deyerl; Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, University of Toronto) |

Renaissance

Renaissance literally means "born again". Webster's dictionary defines

it as a transitional movement in Europe between the Dark Ages and modern

times, beginning in fourteenth century Italy and lasting into the seventeenth

century, adding that the period was "marked by a humanistic revival of

classical influence expressed in a flowering of art and literature and

by the beginnings of modern science". While this is true, it is really

only half the story -- the humanistic half. The invention of the printing

press about 1465 brought about the Renaissance. For the most part, the

printing presses reproduced the Greek works and Bibles, although as might

be expected there is evidence of a flourishing little business in pornography.[18]

The Greek works were translated into Latin for the scholars and the Bibles

began to be translated into the local tongue for the common people. The

Greek works reintroduced some positive knowledge but this was generally

outweighed by the gross scientific errors of Aristotle and Galen and the

dark practices of diabolism from such writers as Hermes Trismegistus.[19]

The Bible, on the other hand, brought a spiritual revival, an exodus from

the old Latin church, and the eventual schism in Christendom.

The Scientific Method

The name Bacon occurs twice in English history. Three centuries elapse

between the first and the second, but it is the second who is important

in the development of the way we think, and particularly the way scientists

think. Francis Bacon was a member of the Church of England and spent his

life in law and politics. As an educated man, he had been required to study

the classics, which meant reading such authors as Aristotle in the original

Greek. Although he was unimpressed with Greek science, and particularly

with Aristotle, he was undoubtedly influenced by that philosopher's principles

of induction as the proper method for scientific investigation.

Francis Bacon, 1561-1626. A scientist-philosopher of socialist ideals. (Engraved by H. Wright Smith after an old print by Simon Pass; John P. Robarts Research Library, University of Toronto) |

The Baconian principles of inductive reasoning consist of making

some initial observations and then proceeding, from experiment to experiment,

until, by reasoning, a satisfactory explanation for all the results is

obtained. What is implicit in this "art", as Bacon refers to it, is that

from the first observation some speculative idea -- spoken of more elegantly

as "working hypothesis" -- is necessary. Then the first experiment is designed

to test that idea. For example, by observation the human senses may tell

us that heavier objects fall more rapidly than lighter objects. To test

this hypothesis, the simplest experiment would be to let two dissimilar

objects fall at the same time from a tall tower and see which one reaches

the ground first. In fact, both objects would reach the ground at the same

time unless one happens to be, for example, a feather, in which case another

more elaborate experiment would be required to remove the effect of the

air. From such an experiment the theory of gravitation was derived, and,

after no exceptions could be found, the theory was declared to be a universal

law. It is still valid today.

This is all rather mundane to our twentieth century way of thinking, and we might assume that scientists faithfully follow the Baconian method, but this is not always the case. The problem is a human one; it seems all too often that when experiments are not possible the theory tends to become hardened into fact in the mind of the theorist by the first few observations. Name and reputation become attached to the theory, as in the case of Einstein's theory of relativity or Darwin's theory of evolution; it takes a truly great man to continue to report all the evidence, even contradictory evidence, and thus risk loss of status (Polanyi 1955).[20] |

Sir Francis Bacon wrote his best-known work, Novum Organum, during

his chancellorship under James I of England, in 1620. In the Novum he

suggested some evolutionary ideas for the origin of species (Bacon 1876,

380). Shortly after the release of the publication, he was dismissed from

his position on a charge of bribery and retired to write New Atlantis,

which

appeared posthumously in 1627 (Hesse 1970; Webster 1924).[21]

In this Utopian work describing the ideal scientific society, he proposed

that scientists join together in institutions and pool their work and ideas.

This socialist ideal gave birth later to the Royal Society in London, the

forerunner to today's research institutions (Crosland 1983).

The French Connection

René Descartes, described as the "father of modern philosophy", was educated by Jesuit teachers and throughout his life remained a Roman Catholic. A first-rate mathematician, his philosophical method was to think rationally from first principles. The worldview of his age had been based largely upon biblical revelation or, in the case of geocentricity, on what was perceived to be revelation. Discoveries in science were beginning to change that worldview, and in the turbulent sea of conflicting beliefs, Descartes chose science as his anchor point. Science, however, relied on the evidence of the human senses, and, while this seemed secure enough at first sight, Descartes began to question if the human senses were reliable for knowing and concluded that they are not. He resolved to doubt everything that could be doubted, and concluded with his famous dictum Cogito ergo sum -- the most elemental point of self-awareness: "I think therefore I am." Although this statement contains a logical redundancy, it was for Descartes the lowest of all points from which he began to build a rational philosophy (Brown 1977).[22]

Descartes tried to extricate himself from the dilemma of obtaining knowledge

through the senses by arguing that since God is good, he would not let

man be deceived by his senses when they operate normally. This argument

is not without its problems, however. How does one know what is normal?

Furthermore, his position contains the implication that man is good and

therefore not subject to self-deception. But self-deception is caused by

preconceived ideas or prejudice and lies at the very root of many problems

in science, as we will see in subsequent chapters. Preconception causes

us to hear only what we want to hear and to see only what we want to see,

sometimes even seeing objects of our expectations, objects that do not

exist. All this is well known to researchers today, yet preconception still

leads to erroneous interpretations of data.

| A rather frightening outcome of Descartes' philosophy began with his Discourse on Method, published in 1637. In this he saw the universe as a mechanism governed by mathematical laws. He attempted to formulate these laws, and, as it happened, the formulations were incorrect. But the idea that the universe operated strictly according to mathematical laws was confirmed by the laws of gravitation, discovered and published by Isaac Newton in England in 1687. This was a signal victory, for it encouraged the belief that human inquiry into nature could be made unaided by revelation from Scripture. The pattern was set for others who looked for similar laws governing not only every aspect of nature but also human relationships, society, government, and more recently the human mind. The consequences of finding such laws leaves man with the impression that divine intervention is unnecessary, and that there is no free will, thus reducing the universe, all life, and man himself to mere mechanism. Descartes had actually gone this far in his own thinking, and he had committed these ideas to a thesis, Traite de l'homme, written in about 1630. Here he argued that animals and the human body are only mechanisms. Following Galileo's condemnation in 1633, the Traite was wisely published posthumously, thus avoiding censure by the church. Nevertheless, this work and all of Descartes' other works were subsequently placed on the Catholic Index of Forbidden Books. |

René Descartes, 1596-1650. Descartes, a mathematician and physiologist, searched without success for the human soul and concluded man was merely a mechanism. (Engraving after the portrait by Franz Hals; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Descartes was a follower of Aristotle, generally adopting his views, except for those concerning the soul. Aristotle had maintained that the soul did not separate at death. This view had become common, with the result that the dead were required to be given a Christian burial and the body not defiled for fear of interfering with the "sleeping soul". Knowledge of the existence of the soul is only given by revelation, but to Descartes' rational mind this was not acceptable as a scientific precept. His senses of sight and touch had not found the soul during his extensive work in physiology. Therefore, he reasoned, the soul, like "body humours", was probably mythical. On the other hand, if the Platonic idea of a separable soul had any truth to it, the soul would never be found for study in a dead body.

Descartes couched these thoughts in hypothetical terms in the Traite,

which

proved to be the first cautious step towards modern dualism, the view that

the mind and body are entirely separate entities (Fodor 1981).[23]

This notion had the effect of both denying and acknowledging the existence

of the soul. This may sound very abstract, but it did result in practical

changes of viewpoint that allowed human bodies to be dissected with ecclesiastical

approval, assuring the progress of medical science. Interestingly, however,

modern developments in medicine, such as those pertaining to psychosomatic

disorders, have brought the Cartesian view of the soul under general criticism,

leaving the profession with the awkward choice of having either to affirm

or deny the existence of an entity for which there is not a shred of direct

and undeniable scientific proof (Brown 1971).

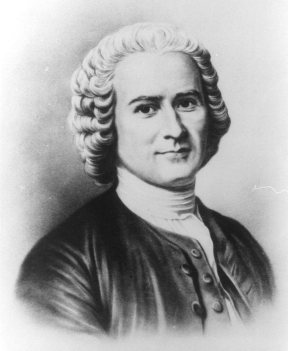

Jean Jacques Rousseau, 1712-78. Denied the biblical Fall of man and maintained that man would retain his inherent goodness if he lived the simple life. (Pastel portrait by Georges La Tour; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

Jean Jacques Rousseau was born in a Protestant home, converted to Roman Catholicism, then finally renounced Christianity completely, becoming what was popularly known as a "free-thinker" among the intellectual set in Paris (Beer 1972). As a Deist he categorically denied all biblical miracles and relegated God to the role of absentee landlord, in much the same way as had Aristotle and Descartes. In contrast to the tried and established Christian teaching that holds that each man is responsible for his own moral life and must strive to avoid personal evil and sin, Rousseau made himself believe that man is born good and is corrupted only by a bad society. One of the outworkings of this notion was his educational ideal that children should be kept away from the corrupting influences of society and allowed to learn naturally what they want to learn. Not only have Rousseau's speculations no scientific basis, but their author was the least qualified to write about matters such as the education of children: he had abandoned five illegitimate children in a Paris orphanage (Rousseau 1904).[24] Strangely, however, there have since been many who would otherwise pride themselves on their complete rationalism and objectivity, yet who have advocated this type of social change. And so we find that Rousseau has left a lasting mark on modern progressive education. |

Reason's Revolution

As has been shown, the Renaissance period produced a number of educated men who had become disenchanted with orthodox teachings based on biblical revelation, that is, the revelation that had been fused with tradition and a corrupt papacy. It was only natural that this should breed outright skepticism as found in the free-thinkers such as Voltaire and Rousseau. The search for the truth turned these men from revelation to reason as found in the teachings of the classical writers of Greece and Rome. The Greeks were particularly admired during this period. The apparently socialist views of Plato were developed, and even the architecture of the time reflected admiration for the classical Greek period.

The discovery of the great laws of the universe by the developing discipline

of science gave credence to the view that all of reality conformed rigidly

to those laws, and that to understand and discover other laws through science

was the sure promise of power. Moreover, with a universe under law, there

was no place for divine intervention. Through knowledge man was at last

perceived to have gained the freedom to be master of his own destiny. Thus,

the Renaissance marked the beginning of modern science, the beginning of

modern socialism, and the beginning of secular humanism.

Head office of the East India Company, Leadenhall Street, London, about 1800. An early example of the revival of Greek architecture, which was at its heyday from 1820 to 1840. (Engraving by William Watts; Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library Board) |

It does not require great insight to see that power in human society takes the form of a pyramid, in which the mind-set of the general bulk of the structure largely reflects that of the mind at the top. Indeed, contrary to the common impression, modern governments are set up this way, with the apex of the pyramid often a mere figurehead representing the unseen wielders of power immediately beneath it. To control the apex is to control the nation. The Renaissance had produced a handful of idealists with a Utopian dream, and while efforts were made to exert their influence on the highest echelons of power in England, the power structure of the Roman church and the nobility in France was evidently too well entrenched to be overthrown purely through connivance. In England, the intellectual approach proved to be more successful, working within the milieu of the Industrial Revolution, but it took the entire nineteenth century and a good part of the twentieth to turn around the mind-set of much of the populace to accept a new social order. In France, at the end of the eighteenth century, more radical means were necessary: a revolution by the people was seen to be the most expeditious means to a noble end and the blood shed but a small price to pay. It was believed that Utopia would be a reality within months once the wheels of revolution were put in motion. |

The usual version of the causes of the French Revolution is that a grain

shortage triggered rebellion in a people who had long been oppressed by

a corrupt nobility and clergy. Many writers have observed, however, that

there were other underlying causes, providing ample documentation to make

their point. Lord Acton, in his Essays on the French Revolution, writes:

"The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult but the

design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating

organization. The managers remain studiously concealed and masked; but

there is no doubt about their presence from the first" (Reed 1978, 136).

| It would be inappropriate here to spell out details such as the intrigue that engineered the grain shortage, but the outcome of the revolution, in which many thousands lost their lives not only in riots but especially in the Jacobin reign of terror that followed, was that king and church were swept away and the new socialist state proclaimed a republic. As a nation France had overthrown the rulership of God, no matter how tenuous that rulership was seen to be, by disposing of their divinely appointed king. In his place the revolutionaries elected a committee of godless men to govern by human reason. Historian Walter Scott describes how all this was publicly acted out: In 1793 the Legislative Assembly, in a united voice, renounced unanimously the belief and worship of a deity. Afterwards, a great procession was staged by the National Convention, which was the government of the day, and mounted on a magnificent open wagon was the Goddess of Reason -- generally recognized as Demoiselle Candeille, a dancing girl from the opera, fair to look upon but of doubtful virtue -- who was paraded from the convention hall to the cathedral of Notre Dame. There she took her place as the deity, by being elevated onto the high altar to receive the adoration of all present. This was followed shortly afterwards by the public burning of the Bible, and the whole scene was reenacted several times throughout the country (Scott 1827, 2:306). |

Statue of Liberty presented by the Freemasons of France to the United States in 1886 to celebrate the centenary of the 1776 Revolution. The Revolution was not as successful in its aims as the French and the presentation was late. (Author's collection) |

Almost overnight, and by devious means, France had gone from Roman Catholicism to atheism to pagan idolatry; the few who had discovered, as Luther had earlier, that divine revelation was the surer way to the truth, had been banished into exile or lay in the grave. To all outward appearances the small number of idealists, who believed that human reason alone was the pathway to Utopia, were supremely victorious. Having made the radical change in social order, the time was ripe for other radical changes: the traditional weights and measures were replaced by the metric system, which has since moved from country to country, hand-in-glove with socialism. There were even serious moves to metricize time with a ten-hour day and a ten-day week, but, fortunately for the rest of mankind, the long-suffering Frenchman refused to accept this, and it never came into general use.[25]

The socialist victory was, however, short-lived, and by 1815 the monarchy

was invited back in and remained for several years. In the meantime the

Roman church also reestablished itself, though not with its previous power.

It seems that since that infamous day in 1793 when rule by man formally

replaced rule by God, there has been in France an uneasy political atmosphere

as one republic supersedes another, each slipping ever surely a little

more to the left. The Utopian experiment, which began in violence, has

not had a record of unqualified success. The object of every revolution

is to bring about a universal happiness, and this was surely declared in

the French revolutionaries' principle of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

After almost two hundred years we see the result of their efforts, and

they are not enviable. Of liberty, there is not a shred left; of equality,

there is scarcely a trace; while of fraternity, there has never been a

sign. Yet in spite of such observations and the dismal record of industrial

growth of that nation throughout the nineteenth century and for much of

the twentieth, the socialist ideal spread throughout Europe and, in its

wake, toppled the crowned and mitred heads of authority.

|

|

| << PREV |

|