|

by Luther Sunderland · ©1988 · PREV NEXT |

|

by Luther Sunderland · ©1988 · PREV NEXT |

Darwinism and Science

Charles Darwin originated nothing really new in his book The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life. The theory that everything had evolved by some natural process rather than being created by a supernatural power had been around for many years. In fact, it was one of the very oldest religious concepts. Some of its tenets, like the eternalness of matter, were included in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enuma Elish. Evolutionary ideas can be traced through the philosophies of many ancient nations, including the Chinese, Hindu, Egyptian, and Assyrian. The Egyptians, for example, had long believed in the spontaneous generation of frogs after the Nile had flooded, and the Chinese thought that insects appeared from nothing on the leaves of plants. The first to elucidate the theory of evolution in a clear, coherent manner, involving a simple-to-complex progression, was Thales of Miletus (640-546 B.C.) His was the first name to be mentioned in Greek science. He began with water which developed into other elements. These first elements developed into plants, then into simple animals, and finally into more complex forms like man.1

Evolutionary concepts were handed down through the Greek philosophers, such as Plato and his pupil Aristotle, all the way to Darwin's grandfather, Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802). "Darwinism" was a term first applied to the evolutionary ideas of Erasmus Darwin, a well-known physician in England. His grandson Charles was quite familiar with the concepts of evolution that Erasmus Darwin and numerous others were discussing in the early 1800s.

As a well-known personality in England, Erasmus Darwin was an important pioneer and spokesman for the early evolutionists. In addition to serving as a prominent physician for nobility, he wrote philosophy and poetry. The two questions he asked about origins were: Did all living creatures, including man, descend from a single common ancestor and, if so, how could species be transformed from one to the other? In support of common-ancestry evolution, he assembled a surprisingly modern-sounding list of arguments based on embryology, classification, fossils, and geographical distribution. According to Richard Leakey and Roger Lewin in Origins, the question about a mechanism was "trickier to deal with", but Erasmus Darwin's treatment contained the seeds of almost all the important principles of modern evolutionary theory. He thought that overpopulation, competition -- even between males and females -- and selection were involved. He also believed that plants should not be left out of the evolutionary picture (as they virtually are today). He seemed to accept the possibility that the principal force in animal evolution was active adaptation to environment, including inheritance of acquired characteristics.2

Charles Darwin was born in 1809, seven years after his grandfather's

death. Although he did not have the opportunity to discuss evolutionary

ideas with his grandfather, he did read his book. According to Gertrude

Himmelfarb in her biography Darwin and the Darwinian Revolution, Darwin

relegated his grandfather Erasmus to a footnote in his "Historical Sketch"

as having anticipated the views and erroneous grounds of opinion of Lamarck.3

It does seem rather inexplicable that Darwin failed to give his grandfather

any recognition for his contribution to the theory of evolution which he

presented in The Origin as though it were an original idea.

A Frenchman, Jean Baptiste de Lamarck (1744-1829), pursued the idea that acquired characteristics could be passed on to offspring, as suggested by Erasmus Darwin. His most famous example was the neck of the giraffe, which was supposed to have resulted from stretching to reach higher and higher vegetation as a drought dried up the lower leaves. Lamarck brought considerable criticism upon the theory of evolution. In 1813 three men independently presented rebuttals of Lamarck-ism at the Royal Society in London, and they all supported the concept of natural selection. Regardless of his own criticism of it, Darwin still occasionally yielded to Lamarckism when writing his 1859 book, resorting to it to explain the origin of the giraffe's long neck.

In What Darwin Really Said, historian Farrington recognized Darwin's lust for fame and thus his failure to acknowledge the previous contributions by others: "No reader, however, could guess from the opening page of The Origin that descent with modification had a long history before Darwin took up his pen." He showed how Darwin pretended to have just stumbled upon the idea while on the Beagle and upon his return home. After talking about "that mystery of mysteries," Darwin wrote, "After five years' work I allowed myself to speculate on the subject." Not a word about his grandfather Erasmus, Lamarck, or any of the others, like Matthew, who had written about the subject in 1831: "Those only come to maturity (who have survived) the strict ordeal by which nature tests their adaptation to her standards of perfection and fitness to continue their kind by reproduction." Farrington notes, "The subject was in the air, and Darwin does not say so."4

Evolutionists, however, did not have exclusive claim to the concept of natural selection: one of the chief proponents of creation, the only rival view, accepted it. Before Darwin, one of the most popular books on origins was Paley's Natural Theology or Evidences of the Existence and Attributes of the Deity collected from the Appearances of Nature (1802).5 Historian Farrington wrote that Darwin was quite familiar with Paley's book: "Darwin read him with delight and found his logic as cogent as that of Euclid."6 There can be no question that Paley's arguments for natural selection were well-known to Darwin. As Gould noted in Science magazine, "Darwinians cannot simply claim that natural selection operates since everyone, including Paley and the natural theologians, advocated selection as a device for removing unfit individuals at both extremes and preserving, intact and forever, the created types."7 He said that all Creationists accepted natural selection and that Paley's book contained many references to selective elimination.

Creationist Edward Blyth, in 1835 and 1837, wrote articles for the British Magazine of Natural History in which he proposed the same idea that Darwin claimed to have thought of a year later. Blyth wrote regarding food gathering in animals, "The one best organized must always obtain the greatest quantity; and must, therefore, become physically the strongest and be thus enabled, by routing its opponents, to transmit its superior qualities to a greater number of its offspring." Clearly, this is natural selection and survival of the fittest in the purest sense. Darwin is known to have been familiar with this magazine and so would have read Blyth's articles. Evolutionist Loren Eiseley has asserted that Darwin got the whole idea from Blyth. Darwin's biographers puzzle over his failure to give credit to others before him who wrote publicly about evolution through natural selection. It was rather ungentlemanly of him.

The Creationist and evolutionist views on natural selection differed in that Creationists thought it was a conservative principle while evolutionists saw it as a force that worked in conceit with random changes to create every living thing from a common ancestor. Evolutionists claimed that natural selection took the randomness out of random variation and made it a directional, creative force which drove certain living organisms inexorably to higher levels of complexity.

The major contribution made by Charles Darwin when he published his famous book in November 1859 was to open an attractively packaged Pandora's box and release it to a waiting world. His book simply served to popularize an existing idea which skeptics of the then widely accepted Genesis account of creation welcomed with open arms.8 Previously, they had no single cohesive text that seemed to tie it all together and offer a possible mechanistic explanation for everything. The Origin attempted to explain the origination of the great diversity of life without the necessity of any divine power, as historian Gillespie emphasized in his 1979 book Charles Darwin and the Problem of Creation.

Besides his lifelong wrestling with the question of religion and origins, Darwin was a man of many conflicts and inconsistencies. In the latter part of his school life he became passionately fond of shooting and he said, "I do not believe that anyone could have shown more zeal for the most holy cause than I did for shooting birds. Yet he thought it was wrong to kill an insect and took to collecting those that he found already dead. In his autobiography (1882) he wrote, "I almost made up my mind to begin collecting all the insects which I could find dead, for on consulting my sister, I concluded that it was not right to kill insects for the sake of making a collection." He had a strong taste for fishing but could not stand putting a live worm on a hook. He explained, "I was told that I could kill the worms with salt and water, and from that day I never spitted a living worm, though at the expense, probably, of some loss of success." So the current idol of the biological world could not kill a fly or put a live worm on a hook, but he had the utmost zeal for shooting birds.

Darwin portrayed himself as a rather dull student, writing that school was "simply a blank. During my whole life I have been singularly incapable of mastering any language." He said that he "could never do well at verse making." Although he could learn 40 or 50 lines of poetry while in morning chapel, he totally forgot them within two days. He wrote, "I believe that I was considered by all my masters (teachers) and by my father as a very ordinary boy, rather below the common standard in intellect."

Charles Darwin's physician father wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, so he sent Charles to medical school at the University of Edinburgh. There Charles soon discovered that he did not have the stomach for such work. He thought that the lectures on anatomy were dull and the subject disgusted him. During his second year he attended lectures on geology and zoology, but said in his autobiography, "They were incredibly dull. The sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on geology or in any way to study the science. Yet I feel sure I was prepared for a philosophical treatment of the subject." Although Darwin's admirers contend (like Niles Eldredge did on a 1983 Boston television program) that Darwin was a geologist, he certainly never claimed to have formally studied the subject. He preferred only a "philosophical" treatment rather than a scientific study of geology. In his second year he dropped out of medical school. Since lack of money was not a problem for the Darwin family, he took up the more carefree pursuit of hunting game and collecting insects.

Not pleased to see Charles waste his life as "an idle sporting man," his father, although an atheist, decided that the lot of a country parson would be a more respectable profession, so he sent Charles off to divinity school at Cambridge University. Charles Darwin initially did believe in God and the Bible. In his autobiography he wrote, "I did not then in the least doubt the strict and literal truth of every word in the Bible." But while at Cambridge he began questioning his faith. He wrote about his years there as follows: "During the three years which I spent at Cambridge my time was wasted, as far as the academical studies were concerned, as completely as at Edinburgh and at school. I attempted mathematics, and even went during the summer of 1828 with a private tutor (a very dull man) to Barmouth; but I got on very slowly. The work was repugnant to me, chiefly from my not being able to see any meaning in the early steps in algebra." He said that Cambridge was worse than wasted because he got into a sporting set, including some "dissipated low-minded young men ... we sometimes drank too much with jolly singing and playing cards afterwards."

Nothing at Cambridge gave Darwin as much pleasure as collecting insects and he even got sketches of some of them published in a book. He concluded, "It seems therefore that a taste for collecting beetles is one indication of future success in life!"9Few historians would agree that it was his insect collecting that brought him fame. Rather it was being the first to publish a book that released the catch on a Pandora's box for a waiting world.

Darwin was quoted in the book Life and Letters of Charles Darwin as writing, "I gradually came to disbelieve in Christianity as a divine revelation.... Thus disbelief crept over me at a very slow rate, but was at last complete. The rate was so slow that I felt no distress."10 Following graduation, two days after Christmas 1831, he set sail as a naturalist on board the British ship H.M.S. Beagle. During a five-year around-the-world voyage and shortly after his return to England, he came to accept the idea of the naturalistic, gradualistic origin of all species that his grandfather had promoted. Later he wrote, "But I had gradually come by this time, i.e. 1836 to 1839, to see that the Old Testament... was no more to be trusted than the sacred books of the Hindus, or the beliefs of any barbarian."11

By 1838 Darwin had adopted as an explanatory mechanism the "survival of the fittest" idea. Many of his admirers credit Charles Darwin with having originated the theory of evolution by the mechanism of natural selection but, as already mentioned, he originated neither concept. Darwin admitted that natural selection was no more than the survival of the fittest idea which Herbert Spencer had described seven years before publication of The Origin in an 1852 pamphlet entitled "Theory of Population." Spencer wrote, "Those left behind to continue the race must be those in whom the power of self-preservation is the greatest -- must be the select of their generation." In another article that year, Spencer had expressed his firm belief in evolution which, through "insensible gradations" plus an infinity of time, could be supposed to produce man from a single-celled creature: "Surely if a single cell may, when subjected to certain influences, become a man in the space of twenty years, there is nothing absurd in the hypothesis that under certain other influences, a cell may, in the course of millions of years, give origin to the human race."

Historian Bert Thompson contends that no person, other than perhaps

geologist Charles Lyell, had as much influence on Darwin as Herbert Spencer.

Spencer was a prolific writer; he produced a ten-volume work on philosophy

and many other books on topics such as biology, theory of population, and

social statistics. Before he wrote on evolution, a dominant theme running

through his writings was an abhorrence of anything supernatural. Speaking

of his years between ages 18 and 20, he told how he slowly lost his religious

beliefs:

Their hold had, indeed, never been very decided: "The Creed of Christendom" being very evidently alien to my nature, both emotional and intellectual.

This anti-supernatural bias was thus developed before Spencer accepted

the theory of evolution and it apparently prepared the soil for the seed

of this theory. Four years before Darwin's Origin of Species

was

published, Spencer told why he had adopted evolution:

Save for those who still adhere to the Hebrew myth, or the doctrine of special creations derived from it, there is no hypothesis but his hypothesis, or (else) no hypothesis. The neutral state of having no hypothesis can be completely preserved only so long as the conflicting evidences appear exactly balanced: such a state is one of unstable equilibrium, which can hardly be permanent.

Spencer admitted that he adopted the evolutionary hypothesis for

religious reasons in spite of scientific evidence against it. He wrote,

"For myself, finding that there is no positive evidence of evolution ...

I adopt the hypothesis until better instructed." In addition to the "survival

of the fittest" idea which Darwin borrowed, Spencer had suggested many

ideas concerning evolution.

Another pre-Darwinian who must be given credit for his contributions

to the development of the evolutionary hypothesis is a Frenchman, Jean

Baptiste de Lamarck, who died in 1829. He was a botanist and zoologist

at a famous natural history institution in Paris, now known as Jardin

des Plantes. Lamarck became one of the world's authorities on the classification

of vertebrates. He was a brilliant scholar and a committed evolutionist,

according to Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky, who wrote:

The first complete theory of evolution was that of Lamarck (1809). It contained two elements. The first and more familiar ... is that organisms are capable of changing their form, proportions, color, agility, and industry in response to specific changes in environment.... Lamarck was the first modern naturalist to discard the concept of fixed species, and instead view species as variable populations. He was the first to state explicitly that complex organisms evolved from simpler ones.12

Lamarck proposed a tree of life, or phylogeny, based on the assumption

that every form of life came from a common ancestor in a single evolutionary

process. Evolutionist Ernst Mayr of Harvard noted: "Stirrings of evolutionary

thinking preceded The Origin by more than 100 years, reaching an

earlier peak in Lamarck's Philosophie Zoologique in 1809." It was

in this book that Lamarck suggested the doctrine of acquired characteristics

for which he has become so famous.

Biographer Himmelfarb wrote that it was "indubitably true" that the ideas Darwin presented in The Origin had already been discussed and that "men's minds were prepared for it" before Darwin first published the book.13 It was thus no mere coincidence that another naturalist, Alfred Russell Wallace, should write a paper in 1858 which described virtually the identical evolutionary hypothesis that Charles Darwin had been discussing with close friends. When Darwin read Wallace's paper, he quickly wrote one of his own and both papers were read at the same meeting of the Linnean Society in London in 1858 with Darwin and Wallace as co-authors. But Darwin was destined to steal almost all of the limelight.

Darwin published a more definitive work the next year in his well-known book The Origin of Species. Darwin's book captured the imagination of a body of people with a particular philosophical bias who then rallied around it, unleashing a force that gradually overcame almost all ideological opposition. In this respect, Darwin has had a more significant impact on every facet of society throughout the world than any other person in the last several hundred years. To some degree, the theory of evolution has influenced the fields of philosophy, economics, education, science, politics, and, to no minor degree, all major organized religious denominations, which now teach it exclusively in their seminaries, either implicitly or explicitly.

Today, however, despite this tremendous record of success, Darwinism is not faring well. In fact, some authors like Norman Macbeth are claiming that it is actually dead and lacks only the final burial. But why is it in trouble after scoring such a sweeping victory? Simply because of its major weakness.

About 20 years ago some scientists discovered a serious problem with the theory of evolution and became very upset that they had been misled to think that it was as well-established as the law of gravity. Consequently, an increasing number of scientists and others have been waging a campaign in public education to expose this major problem, as well as other flaws in the theory, and let the public in on what even some evolutionists admit has been a carefully guarded "trade secret."

The paradox is that the Achilles' heel of evolution theory turned out to be the very problem that troubled Darwin the most, namely, the lack of any fossil evidence to support the supposition that all life had come from a common ancestor. Indeed, although Darwin fervently hoped that further geological exploration would vindicate his theory, the fossil record has become "Darwin's enigma."

Only Two Theories on Origins

Often, in debates on origins theories, evolutionists assert that there could be many mechanistic theories of how living things originated. In his interview, however, Dr. Patterson said that he knew of only one theory besides gradualistic evolution -- what Gould and Eldredge were calling "punctuated equilibria." He did not personally recognize "panspermia" (the idea that first life had been transported to earth from outer space) as a satisfying solution because "that just puts the problem somewhere else." He said that if it did not start here on earth it might have come by a fleet of rocket ships, but he thought that really did not answer the question.

Dr. Raup said that, if there were a third possibility, it would be interplanetary seeding (panspermia) that should be considered. He agreed with Patterson that it did not really answer the question but just moved it back one planet. In a final exam some years ago, he had asked his students to disprove the proposition that trilobites (an extinct invertebrate) had arrived on earth in a basket from outer space. He found much amusement in their squirming because, as he said, "It's difficult to disprove this." Panspermia was not, he thought, outside the sphere of scientific investigation for "One could look at the data and see if they are more compatible with that idea than any other."

This, incidentally, is not just a frivolous question with which a teacher

can tease his students. It does not take a great amount of thought to see

that evidence for the arrival of life from outer space in a basket and

for the creation of complete life forms by God could be identical. In both

cases, the first evidence of different types of life would show the abrupt

appearance of complete functional organisms with no intermediates connecting

them to anything basically different. So, if it is not outside the sphere

of scientific investigation to evaluate the evidence for panspermia, it

can hardly be claimed that the evidence for creation cannot be evaluated.

If the fossil record showed the abrupt appearance of organisms without

ancestors, that evidence would equally support either panspermia or creation.

| Dr. Eldredge acknowledged that there were just the two concepts, namely, creation and evolution -- the latter being explained by either Darwinism or his theory of punctuated equilibria. Later, he reiterated that there were "only two generally held views" on why we have diversity of life: evolution and creation. When asked if there could be a third, he said that there was a third biological one, spontaneous generation, but he thought that had "been abandoned" by biologists. |

|

When it was noted, "But that doesn't differ from evolution which requires spontaneous generation of the first cell," Dr. Eldredge replied that he did not know. He said that it was in a sense, and then it was not, but there were currently just two theories in vogue. He viewed both as antithetical "sets of assumptions." He said that they were "axiomatic" in the sense that he did not "see one set falsifiable in favor of the other." He had discussed this with Creationists and would not argue the point.

This is a major contention of perhaps all scientists who are Creationists. They contend that no theory of origins can be tested completely and thus cannot be falsified. The reason is that evolution is supposed to be a one-time-only historical event or process that occurred in the past when there were no human observers, and it proceeded too rapidly in the past to have left any fossils. Evolutionists contend that today it is proceeding too slowly to be observed within the lifetime of any human observer. On the other hand, if various life forms abruptly appeared on earth, whether by panspermia or creation, it would have been a unique historical event.

The museum officials seemed a bit uncertain about how to define a general theory of origins. Dr. Patterson thought there were three: Darwinian evolution, creation, and punctuated equilibria evolution. Dr. Raup also thought there were three: evolution, creation, and panspermia. Dr. Eldredge thought there were only two: evolution and creation. Other scientists say there are only two theories that are now seriously considered but, who knows, someone might think of another one someday.

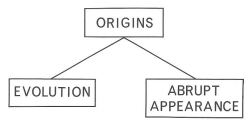

There are really only two general concepts as shown in Figure 1. Life either evolved from a common ancestor, or various different forms first appeared abruptly on earth. The same three general explanations have been offered for both of these theories: purely mechanistic, theistic, or unknown. The mechanistic explanation for evolution is either neo-Darwinism or punctuated equilibria; for abrupt appearance it is panspermia. The theistic explanation for evolution is called theistic evolution, and the theistic explanation for abrupt appearance is creation. The unknown possibilities are simply escape routes for those who do not wish to admit the obvious.

What Is Science?

|

Over the years, man has gradually systematized the quest for knowledge

in order to separate good ideas from bad, fact from fantasy, and what we

commonly call "science" from superstition. Actually, the original meaning

of science was simply "knowledge." Science was a branch of the study of

philosophy. Now it has come to be regarded as man's search for knowledge,

in particular through the testing and falsification of ideas that have

been devised to explain various natural phenomena, processes, and facts

that he has observed. Most people now think of science in the more narrow

sense of "empirical science," or the branch of science that can be tested

empirically in the laboratory, rather than simply knowledge or man's quest

for knowledge. The systematic methodology scientists use in empirical science

is called "the scientific method."

There are specialists who make their life's work out of developing and studying the systematic rules that have been found to be effective in the gaining of knowledge about the natural world. Their field is called the "philosophy of science." Roger Bacon in the 1200s and Francis Bacon in the 1600s are together given credit for originating the experimental method. In his Novum Organum, Francis Bacon established a new methodology for the experimental interpretation of nature.14 It was Bacon's conviction that the mind, freed from the impediments of prejudices and generalizations, could, through knowledge, gain sovereignty over nature. He said that those who looked upon the laws of nature as something already explored and understood did philosophy and the sciences great harm. He criticized the Greeks for trusting too much in the force of their understanding and for making everything turn upon hard thinking and perpetual exercise of the mind. His method was based upon progressive stages of certainty. He stressed reduced dependence upon logic, which can have the effect of fixing errors rather than disclosing truth. Therefore, he proposed that the entire work of understanding be commenced afresh and that the mind not be left to take its own course but be guided at every step. |

The essence of scientific experimentation is for man to be unshackled by preconceived ideas. Progress is to be made by experiment, discovery, and the establishment of fact by the observation of results.

The modern-day Francis Bacon is Professor Karl Popper, German-born philosopher of science now living in England. He has made great contributions to our understanding of science. Nobel Prize winner Peter Medawar calls Popper "incomparably the greatest philosopher of science who has ever lived."15 At a seminar held at Cambridge University to discuss Stephen Gould's ideas on evolution (April 30 - May 2, 1984), Medawar summed up the meeting with the observation that no theory, no matter how well-established, can be considered exempt from Popperian challenge.

Herman Bondi has stated, "There is no more to science than its method, and there is no more to its method than Popper has said."16

Popper strongly supports the idea that a theory in science must be testable and, for the tests to be valid, they must be capable of falsifying the theory if it is not correct. It follows that a true scientific theory, in order to be tested, must be about a process that can be repeated and observed either directly or indirectly. One-time-only historical events may be true, but they are not part of science for there is no way of repeating them, observing them, and subjecting them to testing. Also, for a theory to be testable, it must be possible for those conducting the tests to use it in making predictions about the outcome of the tests. If a theory is not suitable for use by scientists to make specific predictions, it is not a scientific theory. Many scientists agree with Karl Popper on the testability requirement for a scientific theory because, without testing, there can be no unimpassioned selection among available alternatives.

Is Darwinism Testable Science?

According to the generally accepted requirements of a theory in science, could Charles Darwin's theory qualify as a truly scientific theory? Dr. Patterson did not think so. In his book, Evolution, he wrote, "If we accept Popper's distinction between science and non-science, we must ask first whether the theory of evolution by natural selection is scientific or pseudoscientific (metaphysical).... Taking the first part of the theory, that evolution has occurred, it says that the history of life is a single process of species-splitting and progression. This process must be unique and unrepeatable, like the history of England. This part of the theory is therefore a historical theory about unique events, and unique events are, by definition, not part of science, for they are unrepeatable and so not subject to test."17

Of course, what Dr. Patterson calls "the first part of the theory, that evolution has occurred" is the only question under consideration in an evaluation of the validity of the theories on origins. Is it true that all life evolved from a common ancestor or isn't it? He says that the theory that life evolved is "by definition, not part of science." The second part simply postulates a mechanism for evolution if it did occur--mutations and natural selection. No one denies that mutations occur or that natural selection acts as a preservative principle in nature, but since these concepts are not exclusive tenets of evolution theory, they do not help differentiate that theory from its competitor. The only question remaining to be resolved is whether random changes, with the best ones preserved, could create successively higher levels of complexity, resulting in the entire biosphere.

In his interview, Dr. Patterson said that he agreed with the statement

that neither evolution nor creation qualified as a scientific theory since

such theories could not be tested. He liked a quote from R.L. Wysong's

book The Creation/Evolution Controversy that both ideas had to be

accepted on faith. A quote of L.T. More's, corroborating Huxley's comments,

was:

The more one studies paleontology, the more certain one becomes that evolution is based on faith alone; exactly the same sort of faith which is necessary to have when one encounters the great mysteries of religion. . . . The only alternative is the doctrine of special creation, which may be true, but is irrational.18

Dr. Patterson said, in referring to this quotation, "I agree." In

one of their audiovisual displays in 1980, the British Museum of Natural

History included the statement that evolution was not a scientific theory

in the sense that it could not be tested and refuted by experiment. This

devastating characterization of evolution brought a flurry of criticism

from the scientific establishment and the museum quickly removed it from

the display. In any other circumstances the media would have raised the

objection "censorship," but in this case they looked the other way.

What does Karl Popper say about evolution theory? In his autobiography

Unended

Quest he writes:

I have come to the conclusion that Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory, but a metaphysical research programme -- a possible framework for testable scientific theories. It suggests the existence of a mechanism of adaptation and it allows us even to study in detail the mechanism at work. And it is the only theory so far which does all that.This is of course the reason why Darwinism has been almost universally accepted. Its theory of adaptation was the first nontheistic one that was convincing; and theism was worse than an open admission of failure, for it created the impression that an ultimate explanation had been reached.

Now to the degree that Darwinism creates the same impression, it is not so very much better than the theistic view of adaptation: it is therefore important to show that Darwinism is not a scientific theory but metaphysical. But its value for science as a metaphysical research programme is very great, especially if it is admitted that it may be criticized and improved upon.19

Of course, Popper is not saying much for his favored theory of Darwinism

because any wild conjecture "may be criticized and improved upon." This

is quite an admission for one who ridicules belief in theism.

Beverly Halstead, writing in New Scientist magazine, July 17,

1980, commented on Popper's position:

Despite these subtle distinctions, it is not difficult to envisage the enormous encouragement the Creationists take from assertions from the BM(NH) (British Museum display) that the theory of evolution is not scientific.20

Dr. Halstead told the author that his article drew so much attention

to the museum display that it was removed from the museum, and that Popper

felt compelled to make a public statement that would quiet the storm without

reversing or negating his previous pronouncements about the requirements

of a scientific theory. In the August 21, 1980, issue of New Scientist,

Popper

replied:

Some people think that I have denied scientific character to the historical sciences, such as paleontology, or the history of the evolution of life on Earth; or the history of literature, or of technology, or of science.This is a mistake, and I here wish to affirm that these and other historical sciences have in my opinion scientific character: their hypotheses can in many cases be tested.

It appears as if some people would think that the historical sciences are untestable because they describe unique events. However, the description of unique events can very often be tested by deriving from them testable predictions or retrodictions.21

These are reasonable statements. No one ever said that nothing in

paleontology, the history of life on earth, literature, technology, or

science, could be studied through empirical testing. Nor has anyone claimed

that it was not possible to make testable predictions or retrodictions

from postulated unique historical events.

For example, from the hypothesis that all life evolved from a common ancestor through an unbroken chain, it is possible to predict that paleontology would uncover evidence in the fossil record of a gradual progression from single cell to man. Likewise, from the hypothesis that life abruptly appeared on earth in complete functional form, it can be predicted that, without exception, the fossil record should show the first appearance of new organs and structures completely formed, and there should be no transitional forms connecting the major different types of organisms such as protozoa and metazoa, invertebrates and vertebrates, fishes and amphibians, amphibians and reptiles, etc. These predictions can be tested scientifically -- and they have been, repeatedly. Interestingly, Gillespie indirectly admitted this when he wrote, "There were ways in which Darwin's theory could clearly have been falsified. He named some of them. The absence of transitional fossils, however, was not one of them."22 In other words, since Gillespie is a believer in Darwinism, he doesn't think it would be right to test the theory against the only direct scientific evidence, the fossil record, for he knows that evolution would flunk the test.

Professor Popper was careful not to contradict his previous clearly written statements that said, "Darwinism is not a testable scientific theory, but a metaphysical research programme." Metaphysics is not science but rather something more closely associated with religion. His calling the activity "research" does not make it scientific for it is possible to research anything, even the most bizarre superstitions. With his generalization that "very often" testable predictions could be derived from unique events, he did not specifically say that evolution was a scientific theory.

Investigators can test some sub-theory predictions of a general theory, but this does not automatically establish the general theory as a completely testable concept. This can be readily understood by considering the general historical theory that first life came to earth in a rocket ship. The sub-theory that a living organism could crawl out of a rocket ship can be tested, but this does not test whether or not a rocket ship actually brought life from outer space. Similarly, the evolution sub-theory that populations change slightly can be tested, but this does not prove that the general theory of common-ancestry evolution is true.

Many other prominent scientists who are evolutionists admit that evolution

theory is not really science. For instance, in the introduction to the

1971 edition of Darwin's Origin of Species, Dr. L. Harrison Matthews

made the amazingly frank admission that evolution was faith, not science:

The fact of evolution is the backbone of biology, and biology is thus in the peculiar position of being a science founded on an unproved theory -- is it then a science or faith? Belief in the theory of evolution is thus exactly parallel to belief in special creation -- both are concepts which believers know to be true but neither, up to the present, has been capable of proof.23

Dr. Matthews probably did not actually mean to infer that there

was actually such a thing as a "proved theory" since he must have known

that no theory in science is ever really proved in the technical sense.

Theories are only falsified through testing, or they pass the test without

exception until people become tired of testing them. What he must have

meant was that evolution had not once passed the test of comparing its

predictions with the fossil record.

As mentioned previously, Dr. Eldredge was emphatic in his contention that evolution theory was nothing but a body of axioms. He repeated, "We have a body of axioms -- the Creationist has and the evolutionist has -- for which I can't think of a crucial test." The author pointed out that it was nice to talk with someone who did not try to throw in a third -- theistic evolution -- which says that every time a change in the DNA code is needed, God steps in. A third time Dr. Eldredge reiterated the point that neither evolution nor creation could be falsified through testing: "Nonetheless, I can't think of any experiments which I might set up that would reject one theory in favor of the other." This is an extremely significant statement from a prominent scientist who has been leading the national anti-creationist organization, which is waging a battle to maintain the exclusive teaching of only one of these axioms in public schools -- evolution. He explained why he personally had adopted the set of "assumptions" that says there is a "natural process which is creative." He thought that if he adopted this set of assumptions he could then make predictions that would allow him to investigate the history of life. Instead of investigating the fossil record to determine which set of assumptions more closely fitted the facts, he made a prior assumption that he had the answer to begin with. He noticed certain sets of resemblances in living organisms and said that the master question was to explain them. He said, "There are two explanations of course. God had a plan, or as you get away further from a common ancestor you get more modification, so you get a nested set. It seems to me you must accept one or the other axiomatically."

So there could be no possibility of his statement being misinterpreted, he emphasized over and over that either evolution or creation had to be accepted as an axiom for neither one could be tested scientifically. In a November 1986 debate with the author on NBC television in New York City, Dr. Eldredge still maintained that both theories must be accepted axiomatically, and that creation could properly be taught in public schools but not in science classes.

Arthur Koestler wrote about the unscientific nature of Darwinism and

said that the education system was not properly informing people about

this:

In the meantime, the educated public continues to believe that Darwin has provided all the relevant answers by the magic formula of random mutations plus natural selection -- quite unaware of the fact that random mutations turned out to be irrelevant and natural selection a tautology.24

In a symposium at the Wistar Institute in Philadelphia, prominent

English evolutionist Dr. C.H. Waddington made some very pointed criticism

of neo-Darwinism as being a vacuous tautology. In commenting on a paper

by Murray Eden entitled, "Inadequacies of Neo-Darwinian Evolution as a

Scientific Theory," Dr. Waddington said:

I am a believer that some of the basic statements of neo-Darwinism are vacuous.... So the theory of neo-Darwinism is a theory of the evolution of the changing of the population in respect to leaving offspring and not in respect to anything else. Nothing else is mentioned in the mathematical theory of neo-Darwinism. It is smuggled in and everybody has in the back of his mind that the animals that leave the largest number of offspring are going to be those best adapted also for eating peculiar vegetation, or something of this sort; but this is not explicit in the theory. All that is explicit in the theory is that they will leave more offspring.There, you do come to what is, in effect, a vacuous statement: Natural selection is that some things leave more offspring than others; and you ask, which leave more offspring than others; and it is those that leave more offspring; and there is nothing more to it than that.

The whole real guts of evolution -- which is, how do you come to have horses and tigers, and things -- is outside the mathematical theory.25

Norman Macbeth has written a book, Darwin

Retried: An Appeal to Reason, in which he gave an especially perceptive

critique of Darwinism. Noted philosopher of science Karl Popper reviewed

this book and endorsed it, calling it "a really important contribution

to the debate."26

In a 1982 interview, Macbeth had much to say about the major problems with

evolution theory and about natural selection being a tautology:27

First, I think, is natural selection. When you ask all the different evolutionists to identify the real heart of evolution, they'll often give you three or four points -- adaption, the number of generations, mutations, and recombination. They've got a list of things that are supposed to be factors, but natural selection is on all lists and is obviously the dominant theory of all evolutionary discussion. With some people, it is the whole thing, so if you knock over natural selection, the whole structure crumbles.

Was natural selection the mechanism for evolution? He replied that

it was, along with variation:

Variation is there but it does not accumulate, although they assert always that it does accumulate. Then you extrapolate it for another couple of hundred percent of the problem and you're in. Extrapolation is a terrible sin, so they've little foundation. The variation is there. You can see it, of course, in all the forms of dog we've bred, but accumulation and extrapolation are certainly used in a big way by evolutionists.

But isn't natural selection just a weeding out process? Macbeth

explained:

A good evolutionist says it creates because everybody admits that something is weeding out. We are always culling, just as the ordinary operation of an animal's life culls out the really weak ones. A faithful Darwinist says it is creative. Here we have the opposition between evolutionist authors.... Michael Ruse says it can create anything ... largely by slow small changes accumulating. Gould, when you read him very carefully, does not discern that it creates new forms; it can mend and tinker, but it is not producing really big new things.

Gould says that it might tune things up a bit, right? Macbeth replied:

He doesn't go much further than that. This is why he confesses bankruptcy on the macro-evolution problem which Ruse will not confess. Ruse sees no problem at all in macro-evolution but Gould, with a much keener eye for the limitations of natural selection, says we haven't got anything to answer that. He pins his hope for the future on epigenesis which is pure hope.... They think the leap forward would have occurred in the embryological gestation period instead of among mature specimens. To some extent they are pursuing a pipe dream too, hoping to find serious evidence of it.

He told why he wrote that natural selection was an exercise in circular

reasoning:

I argued it was a tautology in my book because it seemed to go round in a circle. It was, in effect, defining survival as due to fitness and fitness as due to survival. I also found people like Waddington saying it was a tautology. He said that at the Darwinian centennial in 1959 in Chicago. Nevertheless, he said it was a wonderful idea that explained everything. Professor Ronald H. Brady goes a little more deeply into it in his long articles in Systematic Zoology28and the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society.29... I will not attempt to summarize Brady's view, but I think it destroys the idea of natural selection and this is certainly the opinion of many people at the American Museum of Natural History. It shoots to pieces the whole basis for the Synthetic Theory.... Few would challenge Brady, but not because they understand and approve.

Did Macbeth think that natural selection could act to preserve life

on earth? His reply:

I think the phrase is utterly empty. It doesn't describe anything. The weaker people die, a lot of stronger people die too, but not the same percentage. If you want to say that is natural selection, maybe so, but that's just describing a process. That process would presumably go on until the last plant, animal, and man died out.

There appears to be a recent practice in certain circles to call

evolution a "fact" and not allow any discussion of its factual status;

simply talk about mechanisms. How legitimate is this? How can a theory

become an established fact? Could evolution be considered an established

fact? Macbeth says that if evolution is defined as simply change, it could

be called a fact since we all agree there is much change, but if you equate

evolution with Darwinism, it is far from being a fact.

What about the oft-heard contention of evolutionists that it is not

permissible for anyone to attack an existing theory until he can offer

a better one? Macbeth is a member of the sys-tematics group at the American

Museum which meets frequently to discuss evolution primarily as it relates

to taxonomy -- the classification of organisms. He has lectured to them

about the fallacy in this argument:

In my lecture to this group, I pointed out that they succumbed repeatedly to the idea that if you want to criticize a theory you ought to offer something better. This I regarded as complete error... it doesn't hold water. There is no duty to put something better in its place. ... I called this the "best-in-field fallacy." ... If the others are all hopeless failures likeLamarckism, orthogenesis, or -- as they used to think -- the hopeful monsters, it doesn't do Darwinism much credit to be a little better than they are. . . . They say this is the best theory, therefore, it must be good.

Gregory Pesely is another author who contends that natural selection

is nothing but a tautology:

One of the most frequent objections against the theory of natural selection is that it is a sophisticated tautology. Most evolutionary biologists seem unconcerned about the charge and only make a token effort to explain the tautology away. The remainder, such as Professors Waddington and Simpson, will simply concede the fact. For them, natural selection is a tautology which states a heretofore unrecognized relation: The fittest -- defined as those who will leave the most offspring -- will leave the most offspring.What is most unsettling is that some evolutionary biologists have no qualms about proposing tautologies as explanations. One would immediately reject any lexicographer who tried to define a word by the same word, or a thinker who merely restated his proposition, or any other instance of gross redundancy; yet no one seems scandalized that men of science should be satisfied with a major principle which is no more than a tautology.30

So scientists who believe in evolution admit that their belief is

based not on scientific examination of the theory, but rather on faith

alone. This does not discourage them from calling evolution a "fact" in

an obvious attempt to promote their belief without being able to justify

it scientifically.

It is generally recognized that the original version of a theory might not be entirely correct but not necessarily false in every respect either. Thus, it is permissible for scientists to attempt to salvage a theory that has flunked a test by making secondary modifications to the theory and trying to make it fit new facts not previously considered. A theory loses credibility if it must be repeatedly modified over years of testing or if it requires excuses being continually made for why its predictions are not consistent with new discoveries of data. It is not a propitious attribute for a theory to have required numerous secondary modifications. Some evolutionists misunderstand this and attempt to point to the continuous string of modifications to evolution theory as a justification for classifying it as the exclusive respectable scientific theory on origins. They often make the strange claim that creation theory could not be scientific because it fits the evidence so perfectly that it never has required any modification. That line of reasoning is like saying that the law of gravity is not scientific since it fits the facts so perfectly that it never needs modification.

Of course, as mentioned above, a theory is never proven absolutely true even if it has not once flunked extensive scientific testing. Its credibility increases until scientists develop so much confidence in it that they stop testing it. Such a highly respected theory is commonly called a "scientific law," like the law of gravity.

Some people mistakenly think that only scientists with a high level of academic accomplishment are entitled to originate scientific theories and that their motivations must meet certain requirements. Actually, a theory can start out as nothing more than a flat guess, a religious concept, or it could be the result of conclusions drawn from a deep study of detailed scientific data. The motivation of the person deriving a theory can be as uncommendable as the desire to win an argument or get a pay raise. As philosopher of science Professor Neal C. Gillespie wrote in his book Charles Darwin and the Problem of Creation, "The source of an idea is irrelevant, in the strict logical sense, to its success in a scientific system or in any other. The procedures of proof in any knowledge system are logically independent of the circumstances of the origin of the ideas involved."31

In striking down the Arkansas "Balanced Treatment Act" in 1982, Judge

Overton contended that the theory of creation could not be part of science

because he thought it could be derived only from a religious document.

This demonstrated his ignorance of the process of science. That is akin

to saying that because evolution is the basis of the first two tenets of

the Humanist Manifesto (the statement of faith of a tax exempt religious

organization) then it could not be true or be part of science. Indeed the

manifesto, signed by a number of prominent evolutionists, does read:

Tenet 1: Religious humanists regard the universe as self-existing and not created.Tenet 2: Humanism believes that man is a part of nature and that he has emerged as the result of a continuous process.

Using Judge Overton's kind of logic, one would be compelled to exclude

evolution from science because many of the original formulators and promoters

of the theory such as Herbert Spencer (an atheist), Charles Darwin (an

agnostic), and Thomas Huxley (an agnostic) had religious motivations. It

is undoubtedly true that these men first became anti-Creationists and non-theists

on religious grounds. But this has no bearing on whether or not evolution

might be the correct explanation of origins or whether it meets the requirements

of a scientific theory. The resolution of those questions is a matter entirely

separate from the motivation issue.

In any case, before a theory is subjected to extensive testing by others, it is technically termed a "hypothesis." The most important qualifications for a scientific theory is that it be testable, and naturally, it must never have flunked a valid test in its most mature form. So the questions that proponents of evolution theory are obligated to answer are: Can evolution theory be subjected to repeated valid tests, and, if so, can it pass those tests?

If there is any test that evolution theory should pass, it is an evaluation against the fossil evidence, even though, as Karl Popper asserts, you cannot prove history scientifically. Though evolution theory postulates that there has been an unbroken succession of organisms connected to a common ancestor, it would not absolutely prove the theory if some evidences of that series were actually found in the fossil record. But it would be difficult to deny that this would be overwhelming evidence in support of the theory of evolution; its credibility would be considerably elevated. Nearly everyone agrees with that. However some people peculiarly deny that it would falsify the theory or even raise serious questions about its credibility if no evidence of such a series of intermediate forms were found after over a century of intensive searching.

A major reason that the theory of evolution is not a falsifiable scientific theory seems to be that it is so plastic it can explain anything and everything. For example, Dr. Raup thought that evolution theory was falsifiable, but when asked why it had not been falsified when no intermediate forms had been found in the fossil record, he explained that the theory had just been modified to fit the evidence: "Well, whether it's valid or not, it's still possible to rationalize the lack of intermediates -- rationalize it by simply modifying the original Darwinian theory."

It was then pointed out to him: "In debates, people say, 'Sure, the original Darwinian theory has been falsified, but we'll come up with a new one as fast as you can disprove the old ones.'" He acknowledged that this was true: "I think that's true of any conventional wisdom."

The author replied, "But that's not science. You've got to have a theory which is subject to falsification, and if it's falsified, throw in the towel. Now if you want to come up with a new theory, okay. But after it has been changed a hundred times and it is still falsified, at some point someone ought to throw in the towel. Maybe you could say, 'We don't know,' but don't put it in the textbooks and say it has been proven as well as any fact of science."

Dr. Raup replied, "Yes, I'm sure you've seen how slowly conventional wisdom dies and it really takes overkill."

But regardless of whether or not theories on origins are truly scientific

theories, the fossil record should at least shed some light on the question:

Did the present biosphere originate from a common ancestor or did various

major groups of organisms first appear abruptly on earth? To find the evidence

relating to fossils, it is only reasonable to consult specialists in some

of the world's greatest museums which collect, study, and display fossils.

The following chapters are based primarily upon material derived from the

author's interviews with the officials at five such museums, as well as

from a survey of the scientific literature on geology, paleontology, biology,

and related fields.

|

|

|

|

|