The idea of freedom merits a special point on the axiological scale of any given individual, society and humankind in general. Freedom is something that we seek, but are fearful to apply. The ideologists, political and religious leaders lavish promises on others to keep them under control. Some think of it as an intrinsic personal attribute; others believe it to be just an illusion or another utopia.

While proclaiming its immutability, people are willing both severally and collectively to trade off freedom for the ethereal assurances of security and relief from responsibilities. Here, one may recall the Chamberlain-Ribbentrop Agreement of 1938, which held out the promise of an "honourable peace" "till the end of our time" to the British crown (in exchange for the pledges of non-interference in the civil war in Spain and the recognition of Mussolini's claims in Ethiopia.)

In the age of the post-industrial society and the time of yet another globalisation convolution, the idea of freedom degraded to a blurry promotion slogan, which is mostly associated with the concepts of democracy, as well as (civil and/or human) rights and freedoms. In pursuit of this principle, we gain more rights: to same-sex marriage, reproductive cloning, ban the profession of any religious beliefs, other than ours. We have already won the right to abortion on demand and the right to live by claiming someone else's life represented by the abolition of the capital punishment. As a result, the mother's womb turned into the most dangerous abode, while death row became the safest place to be in a society where rights prevail.

It is helpful to be reminded that as understood today, the term "human rights" originated in the following context, "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness." (The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America) Special rights were granted on the basis of man's special role in the Creator's master plan.

About ten years ago the press ran a piece about a private plane that crashed in the jungles of Amazon. The pilot survived the crash and stumbled across people several weeks later. During those weeks he fed on the crows. Some time later the Animal Rights Association brought a lawsuit against his abuse of crows. Really, if human rights are not predicated on the Creator's plan, then why would a man have a stronger case to eat the crows, than the crows to eat the man?

This illustration may seem comical. However, if we were to look back in history, we would see that the elevated elocutions concerning freedom, equality and brotherhood invariably end up as despotism, guillotine and Gulag in the societies where the concept of human right was made devoid of transcendental meaning. Pursuit of the rights that exceed the authority given to us by the Creator will not bring freedom.

Nor does democracy (i.e. the power of the people) give us more freedom when, to use Bernard Shaw's apt comment, "democracy substitutes election by the incompetent many for appointment by the corrupt few." In practice, it always turns into the ochlocracy (government by the mob led by a "demagogue" [Greek: "one of the crowd," or "leader of the people"]) or oligarchy (government by the few), or plutocracy (government by the wealthy), or tyranny.

To forestall any accusations of political prejudice and disrespect of the convictions of others, I, albeit reluctantly, will refrain from the illustrations suggested by contemporary Ukrainian and Russian life. To describe democracy in action, let us turn to the public unrest of 55 AD in Ephesus (Roman province of Asia, West coast, Asia Minor) as was masterly chronicled by the physician, historian and brilliant writer of the first century AD, Luke the Evangelist. The full story can be found in the Acts of the Apostles, 19:23-40. Although almost two thousand years have passed since the event, some common features can still be easily identified in any movement pursuing democracy.

Because of strengthening globalisation, Ephesus' competitiveness took a plunge resulting in losses for the traditional Ephesian trades. The merchants indignation reinforced by their inaptitude to adjust to the market changes brimmed over and poured into the streets. Aware of the wrongfulness of their own hidden motivations, the merchants kept shouting slogans and reciting catchwords that appealed to the values of their fellow citizens. ("Long live uncorrupted and transparent democracy!" "We will strengthen the ties with the sister nations of Minor Asia!" "Forever with Rome!" "We demand protection for the electoral rights of the physically challenged of Eastern Minor Asia!" "No to corruption!" "The bigger our crowd, the stronger we are!" "Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!," etc.) As the crowd of thousands of people gathered at the city amphitheatre (stadium, central square) "the assembly was in confusion…Most of the people did not even know why they were there." (Acts 19:32) Many politicians try to use this opportunity to publicise their own electoral agenda, but the crowd ignores them. Everybody has their personal reason to be unhappy and nothing but self-interest and demagogic slogans (Greek: "leading the people") unites the people. Few have a clear idea of what exactly their demands are.

Several hours later, when everybody was getting tired of the endless protests, a state official (deputy, secretary, chancellor, or president - someone who lives off the taxes collected from the people) comes out to address the assembly with a moving speech.

Just like a classic performance of a philharmonic orchestra, his speech comprises three parts (you may take notes to only confirm later that any such speech has similar structure.)

- "You." I am honoured to govern such great people as you are. The whole world knows that no other people are like you, men of Ephesus. This is quite beyond doubt, and no one can take that glory away from you.

- "We." We, state officials, exist for the sole purpose of serving you and securing your well-being. We are the ones who make every effort to provide schools, nurseries and retirement for you. We are your servants. Please come to us first, if you have any questions at all. That is what our receptions, departments, commissions, courts, etc., are for. Be sure to come to us, no request will be left unattended.

- "They." I am on your side, totally, and I share your concern. However, this meeting has been assembled with minor violations of the law. Should the higher authorities apply force in bringing order, technically, they will be right to do so. And while, personally, I commiserate with you, there is no way I could possibly stop them. So, let us disband peacefully now and solve all of the problems later, on a case-to-case basis. Please come back, write to us, or call on the hotline.

|

The citizens disperse, satisfied. Nothing changes. Is this what democracy is all about? But how is freedom related to that? What is it, after all, this freedom? How can it be secured? As is the case with "happiness" and "love," for example, the great diversity of definitions suggests that this concept is hard to describe, but easy to identify, if practiced. For instance, why, dear Symposium participants, are you sitting here listening to this amateurish nonsense, rather than climbing up the nearest mobile communication tower and plunging down from it headfirst, so that you can experience the joys of a free fall? We are free people, aren't we? The answer to that is perfectly plain, "We don't want to." It is precisely because of the freedom we have that we do not do what we do not want. This is not our will. And if any well-wisher is going to help us along to experience the free fall, this will be against our will and will not represent a free act on our part.

The conclusion of this superficial example is obvious - freedom involves the possibility to act according to one's will. But then, the concept of unrestrained freedom turns into a lie! Our will naturally limits our freedom.

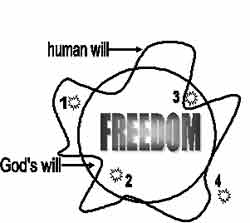

Suppose the plane of Figure 1 represents the field of intended actions. The line that conventionally describes our will shows the limits of our freedom. Everything that is within our will belongs to our free acts (for instance, action 1 and action 2); everything that is beyond our will (actions 3 and 4, for example) is represented by the actions that are not free.

Thus, if our will serves as a determinant of our freedom, then the development of our will will be a natural means of extending our freedom. But we will fail to develop our will if we are to follow the idealistic recipes of Sakyamuni's [Buddha's] extinction of will, or Nietzsche's permissiveness. If we seek perfect freedom, we must perfect our will. This calls for a model, i.e. a perfect will. No individual will, or joint will of a nation, or that of a party or society, is a perfect will. Similar to the source of inalienable freedoms, the perfect will must be ideal, absolute and transcendent. Such is the will of God.

|

Know the truth and the truth will set you free, Christ says. (Jn 8:32) As we bring our will in line with God's (the circle on Figure 2), as we obey it and perceive it as an imperative to assume responsibility for its obedience, the direction which we must choose to perfect and develop our will becomes evident. Thus, action 1, which remains within our will, ends up outside God's will and should be rejected. Action 2 that we desire is within God's will and we may perform it with great satisfaction. Action 3, which is located outside our will, is, nonetheless, within God's will and therefore, we should make every effort to perform it. And last, action 4 is not something that we or God want and we are free to forget about it with no fear of the consequences.

Luke the Evangelist also narrates the story that took place in Europe, more specifically in the Roman colony of Philippi, which was the ancient capitol of the Macedonian state. The event occurred several years before the commotion in Ephesus. (Acts 16:22-34) Paul and Silas, aliens and infidels spreading the ideology foreign to Rome, are charged with instigating a coup d'etat and put in the city jail. Aware that the law provides capital punishment for cases like theirs, the prison warden gives orders to fasten their feet in stocks and lock them up in the inner cell. Experienced in his trade, he knows that those sentenced to death have nothing to lose and will be quick to use any opportunity to escape. If that happens, then according to the laws of the Roman Empire, he will have to face the same sentence as the prisoners, i.e. he will be put to death.

An earthquake hits at night, the warden runs to the jail to check on the prisoners and sees that all doors, locks and bars have been knocked out by the seismic wave. Right where he was, he draws the sword to kill himself to avoid the disgrace. At the last moment before his death he does not have a trace of doubt that the dungeon is empty. Why should he cherish useless illusions? But suddenly he hears someone crying out to him with an Eastern accent, "Do not harm yourself, we are all here!" Unable to believe his own ears, "the jailer called for lights, rushed in and fell trembling before Paul and Silas." (Acts 16:28,29) It turns out that these two prisoners of conscience not only refused to escape, but also gathered around themselves other prisoners - rabble-rounsers, debtors and criminals - who wanted to listen to their story. Why run away if you have something to talk about? For the first time the old warden saw what perfect freedom was really like, the freedom that is free from circumstances. The freedom that cannot be restrained by stocks, bars and locks. The freedom that you cannot help seeing in the missionary Apostle Paul and educator Yanush Korchak, playwright Vaclav Havel and novelist Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and Karol Wojtyla (better known as the Pope John Paul II today), Bishop of the Soviet-controlled Krakow, and in all those who had already found the same. The Holy Scriptures say, "where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom". (2Cor. 3:17)

Being responsible to the Creator is the only way to perfect one's freedom. But this way is not paved by democracy and human rights struggle, which can only in part and very unreliably protect us from arbitrary rule and corruption. The way lies with the understanding of God's will and aligning our own with His standards. "Do not conform any longer to the pattern of this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your mind. Then you will be able to test and approve what God's will is - His good, pleasing and perfect will," the Apostle Paul writes (Rom. 12:2) and calls on those who have stepped on this path to, "stand firm and do not let yourselves be burdened again by the yoke of slavery." (Gal. 5:1)

The U.S. Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776.

Радостная Весть. Новый Завет в переводе В.Н.Кузнецовой. М: Российское Библейское общество, 2001. - 432 с.

Francis A. Schaeffer. How Should We Then Live? Wheaton, Illinois: Crossway Books, 1983. - 288 p.

Scott B. Rae. Moral Choices. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2000. - 282 p.